The Importance of Preschool Vocabulary

It is important to me, as a home school mom and just as a mom, to take advantage of the first 6 years of my children’s life. At this age, they have an “absorbent mind.” It is has been said that anything learned in this period will stick with a child for their entire life. Can you remember your phone number from when you were little? Case in point.

Children are eager to learn at this age, and their learning is so very hands-on. Many authors write about how having an environment rich in learning opportunities is optimal for a child. It indeed builds more than just a vocabulary, but the very brain architecture itself.

I have thus focused on hands-on learning at this age, where I teach definitions of words using tangible materials. I have found, more than any other, these are the most interesting lessons to a child of this age and have the likely most benefit.

It is also my experience that understanding the components of a system allows a person to break up that system in a way as to truly understand it. The focus on the lessons I give to preschoolers is on the simple definition. I have found that having this epistemologically powerful tool–a word–allows the child to understand the world better. As I teach my child these lessons, I notice that they notice the concept often and integrate it into their free play.

I have made several lessons like this, which can be found on The Observant Mom at facebook. I am going to be upping my game in the new few months, and designing near entire curriculum about various topics with their definitions. First up will be the properties of material; next will be emotions; and I have my eyes set on tastes and smells. I am sure more will come in addition. I will also put these on Pinterest for easy reference later.

I haven’t found many resources that have this specific focus on vocabulary at this age. Many do it, of course, but I have not found a grab and go lesson that does this, for this age. Here is my mission statement about how I teach children at a preschool age (3 – 6):

The Observant Mom Mission Statement about Teaching Preschoolers

Teaching the proper definition of words is everything to me when it comes to teaching lessons to preschoolers. I would much rather spend several days teaching one concept and making sure it is taught correctly than giving mass amounts of information and curriculum to my child. Teaching definitions of words is the bridge between toddler learning and elementary learning. Having hands-on experience with many materials and being given the exact word to describe them allows a child to easily follow more abstract lessons later in elementary education. Hands-on experimentation, given to the child in a deliberate and intelligent way, is in perfect alignment with how a preschooler best learns. There is an art to this, contained in this blog post. This drives most of the lessons I do at this age and is much of the philosophy behind the #OneLessonADay that I do with my children, which can be found with that tag on facebook.

How To Best Give Lessons to a Preschooler

These are the principles that through experimentation, I have found are best when giving a lesson to a child:

- Always present opposites, and a continuum if possible

- Get the child involved in a hands-on way

- Give a full and wordless demonstration to start

- Let the child sleep overnight after a lesson before doing any assessment

Always Present Opposites (minimum: 2 objects) and a continuum if possible (minimum: 3 objects)

Through trial and experimentation, I have found presenting three different materials is the optimal number to teach a concept, but two is the minimum.

I will give an example of one lesson that failed, which used only one material. I had tried to teach “fatigue” using a paper clip. I taped it down, but such that the inner part of the clip was loose. I then bent it back and forth, and after about 10 times, it broke. I told my 4-year old that it broke due to fatigue. The very next day, my son started to bend a sponge until it broke, and said “This is fatigue!”

This lesson wasn’t a complete failure. But, my concern is that “fatigue” to him meant “bending something until it breaks,” when other stresses other than bending can cause something to reach its fatigue point. It would have been ideal to have something that fatigues under stress and something that does not. Thus, fatigue and durability would both be taught, which are conceptually complementary, isolating better what is being shown. Minimum number of materials: 2

It is best to use at least two different materials to teach the same concept, which show something that is similar but on opposite ends of some continuum. Always presenting opposites is a key principle to presenting lessons that teach definitions.

If you can add a third material, you show the gradation. I have found that for everything, 3 is usually the ideal number, such as to teach 3 colors at once, or 3 letter sounds. Just 1 item allow no comparison or contrast. Two items allows one comparison. Three items allows 3 comparisons.

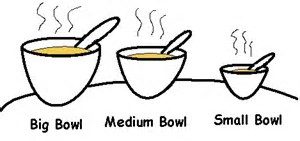

I wonder if this is why The Three Little Bears has such long lasting appeal to children everywhere. There is something about having “hot, warm, and cold porridge” or a “big, medium, and small chair” to cement an idea for a child.

Ayn Rand’s definition of concepts is of note here. In Introduction to Objectivist Epistemology, she writes that all concepts require comparing and contrasting objects. That is so necessary when teaching a child. This book influences how I teach greatly. It’s a dense but short read and worth it. I’ve read it 5 times, and I think I finally got it.

The Genius of Montessori: Get the Child Involved in a Hands-on Way

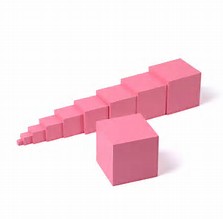

The previously written is built in to Montessori. For instance, with pink cubes, there are 10 cubes. Everything is the same except size, thus it teaches size. Size is the continuum and you can teach the logical opposites, “big” and “small” with it. And certainly gradation is built in with 10 cubes.

Montessori takes the child through the Three Stages of learning, where they are given a lesson with the proper word (Stage 1) and then 2 progressively harder “tests” (Stage 2 and 3), which is necessary to exercise the child’s mind and to give feedback that they understand the idea.

But before even this, the child is allowed to play with the material. With the pink cubes, the child puts them in order and not until they do this does the teacher give the “big” then “small” lesson. When the child can put them in order, it means their mind is ready to receive the information.

I have found this with virtually all lessons I try with my kids: It is best to always let them play with the material first. I often don’t even worry about giving the right word to describe anything until the child has had an opportunity to do something hands-on with the material. I wait for some indication that they understand the difference in the two materials they are experimenting with to swoop in with the three stages of learning, where I give the word first and then later ask them a few questions about it to see if they learned the concept. And, if they never respond, they never respond. I might try again in 3 – 6 months. Or, if they already show clear demonstration of the concept, I don’t bother with the questions.

I have indeed found that giving the lessons in a hands-on way and doing one or two similar but different lessons (described below) allows my child to naturally master it.

Give a Wordless, Full Demonstration at First

In the document where I keep track of the lessons I do with my child, I have in big letters, “GIVE A FULL DEMONSTRATION FIRST.” I seem to forget this constantly.

I have read before that children can either listen to you or watch you. They can’t do both at the same time. So if you want to show them something, stop talking. If you want to tell them something, stop showing. Whatever I want my child to do with the material, I show them at first. If I talk, I stop using my hands. Make sure the TV is off and there are no distractions.

It’s always a balance with these lessons of where the demonstration ends and then the child can take over. These lessons are more ambitious than typical Montessori lessons. In my experience, if you give the demonstration and it’s a hit, the child will likely just take over. If they don’t, it might not have been the best lesson, or it’s the wrong time. I try again or try something different.

Assessment: Let them sleep on it

How and when to asses the child is sometimes difficult. To asses the child, you take them through the Stage 2 and Stage 3 of learning. Stage 2 is a multiple choice question, “Which item item is brittle?” Stage 3 is an open ended question where you ask, “what is this?” and the child has to say, “Brittle.” I am not sure Stage 3 is ever necessary for these lessons.

One thing I can tell you is to never ask any questions of the child immediately after a lesson. If you give a lesson, wait one full night until you ask any questions. There is something about sleeping on it that helps. Montessori writes about this explicitly in To Educate the Human Potential. She discusses the psychology of “engrams” and how the unconscious mind goes to work, integrating data, after it is first learned. How many times have you had a fresh look at a problem when you sleep overnight?

If you do the sorting activity, the hands-on activity and the assessment are built into one. You put “shiny” objects on one side and “dull” objects on the other. The child just showed they know the difference. I have found most hands-on activities allow the child to show that they understand the concept. As my son races around the house, using a flashlight, looking for shiny and dull objects and announces “shiny!” or “dull!”, I know he gets the idea.

I have found that with these activities, it is often best to have two activities to teach the same concept. I describe this below. In coming back to them a few times, I watch as my children naturally master the concept. I find they see the concept in their daily life and demonstrate knowledge of it.

If the child is reading, it’s good to print on a slip of paper the words being taught. You can print a second set of the words, and have the child match word to word.

Assessment is important. Yes, high-pressure testing is awful. But a teacher needs feedback to know if the child is getting it, to know if her lessons are fruitful. And the child needs a chance to exercise their knowledge, because little information sticks unless it’s practiced. Fortunately, the hands-on activities in and of themselves already provide some exercise. And, my assessment focuses more on if they are interested in an activity or not. It is written of preschoolers that just handling material helps them learn. Of course, the entire purpose of these lessons is to give words in an intelligent way, so giving the word of what they are experiencing (stage 1 of learning) is critical and then asking a question the next day (stage 2) is a decent enough paradigm.

Beyond Montessori Materials

In Montessori, for each lesson, everything is the same except what is being taught. As I move to other lessons, this is not entirely possible. For instance, I would love to find materials that are all exactly the same except in how easily they bend, to teach stiff versus flexible, but it’s unlikely to find this.

I have thus found it best to have two different sets of material to teach the same topic. So, to teach “insulation” versus “conduction,” I might have a thermos, which insulates, and a jar, which conducts heat. I would fill these up with hot or cold liquids, and let the child feel these containers and feel the liquid a day after they’ve been in them.

Lesson 1: Thermos and other containers with hot or cold liquid in them

Lesson 2:

Another separate lesson may be to show how a frying pan conducts heat and an oven mitt insulates it.

Lesson 3:

Putting different materials on ice to see which conducts and which insulates was a favorite:

It is also a bit difficult to always find opposites. What is the opposite of “brittle”? Well, brittle is something that is hard and breaks easily, like a twig. Something can be soft and bend easily, like a marshmallow. Something can be hard and not break easily, like a tree trunk. (I picked “malleable” as an opposite, and we did areal fun lesson where we tried to stamp aluminum foil and lasagna noodles to see which stamps and which breaks.) This is advantageous however, because “brittle” will show up in many lessons.

Ayn Rand’s definition of concepts is that it is a process of differentiation and integration. To do this, having more than one contact with the concept is necessary–and I will be the first to submit that more and more contacts will refine the concept. The truth is that the more the child compares and contrasts, the better the idea in their mind. But, we do not have infinite time or resources to teach these lessons. What is the very best way? Challenge accepted. I throw out lessons, try them, and keep refining, and getting better, and looking for other ideas. At some point I may actually organize them in a way as to actually be navigable. For now, they are sprinkled on facebook and on this blog. Check me out, by the way! The Observant Mom.

Powerful Learning Tools

Sorting

Sorting is where it’s at. If you can have something that can be sorted into two piles, you have a winner. It’s hand-on; it can show gradation; and you can give the word immediately. It’s feedback also that they understand it. Here is one on magnetic and non magnetic.

If you just do sorting with the child over and over, it’s a hit. Other activities can be a hit too. I’ll describe them in blog posts about the concepts.

2 thoughts on “‘The Three Little Bears Principle’: How to Best Teach Definitions to Preschoolers”