Hi, I’m Amber, “The Observant Mom,” and I document the age-related stages children go through. These are those times children “act up” at fairly predictable age-related times but on the other side is new mental growth. I have a book series coinciding with this work entitled Misbehavior is Growth. I have books published for toddlers, threes, and fours.

Unfortunately, for age five, I must put this book series on hold. I simply do not have the time, as a mom of three rapidly growing children, to write a book right now. In my books, I otherwise offer educational activity ideas for every milestone, as well as a few parenting tips. I have also found a pattern of child development, which I call a “hill” of child development. Children go “up” into fantasy and then come back “down” to reality in a cyclic fashion, about 2-3 months at a time. I typically offer my analysis about these hills in my books. In lieu of writing a book for five year olds, for now, this blog will have these educational activity ideas, parenting tips and my analysis of the “hills” of child development for age five, albeit in a slightly more generic format. If you want to skip to any of the sections, you can do so here,

The Misbehavior and Growth of Five Year Olds

The Hills of Child Development for Age Five

Top 3 Educational Activities for Five Year Olds

Parenting Tips for Five Year Olds

The “misbehavior” of five year olds

Let’s just get down to it. Five year olds are prank-pulling punks. That they can lie is totally novel to them, and they play around with it, often. You might get handed a cup full of salt and told it is milk. Or you might be handed an unsharpened pencil and told it is ready for use. Children grow in complexity as they do this. They can come up with some rather good pranks, to be honest. Your babysitter is not off limits, by the way.

My child developmental research, which I have been doing on a nearly daily basis for 7 years now, shows that just about everything about a child’s growing awareness of reality comes down to not just if they personally see something but if you see what they see, too. Human consciousness is largely collective. None of us really believe something is true unless someone also agrees that they see what we see. Five year olds are really trying to see if you see what they see and, if not, how they can rectify that situation. This might explain why they are prank-pulling punks, as well as why they might “lie” sometimes. What is real? What is not? Can they trick YOU? That they CANNOT trick you will tickle them. In their late fives, they are especially tickled that they cannot trick you not just over external objects (salt in a cup, etc.), but about who they themselves are. They cannot trick you by pretending to be sleeping, etc. This helps them develop a deeper self-awareness. Children need this. They need you to see them so that they can see them. At four, children developed self-awareness as such. They became aware that they exist and also that they can die. At five, they develop an awareness that you are aware of them.

As far as other difficult behavior, five year olds also really want to know how they can get along with others. In their early fives, when children are outright bad at this, it can cause intense problems. They insert themselves, aggressively, into the play of other children. They also might want an excessive amount of control over other children. This gets better, overall, as they learn to negotiate with others. In their mid- to late-fives, after a long sunny period, children can again get choosy and difficult, possibly even aggressive or controlling at times. There is an intense energy around 5.9 [years.months] that I think is worth noting. At this age/stage, children can be aggressive and even menacing, as if they can’t stay within their own bodies. In their late fives, children become more intensely aware of the larger environment and how they fit in it. They become more painfully aware, for instance, if they are left out of play with other children, which can cause issues. And throughout their mid- to late- fives, children get increasingly harsh, bold, and judgmental.

There are lots of sleep issues for children when they are five. They have many nightmares, too. If you haven’t co-slept at all until now, you might consider it. When you hear of the things they are going through at night, you might understand why it might be so meaningful to five year olds to feel safe near adults at night.

Age five is otherwise, on the whole, a rather pleasant time. Sure, things can get rocky at times. And, sure, some children struggle more than others. But compared to the younger ages, five really does seem markedly pleasant.

The growth of five year olds

To understand child development, as seen through the eyes of a child, I have asked people before to imagine it as if a child is watching a play. In the twos, children start to form a permanent understanding of the background stuff in the play, i.e., the stuff that doesn’t change much, their normal routines, routine holidays, etc. In their threes, they start to see things actively moving about, such as the actors do in a play, which translates to sizing up new places and actions quickly. At four, children realize they are in the play, which was an enormous jolt of self-awareness. In their fives, children perfect their role.

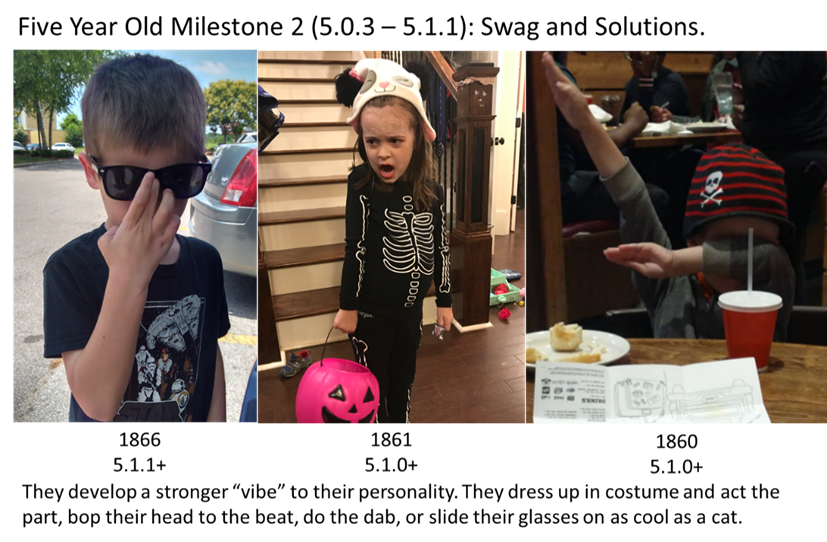

Five year olds are “smooth.” As noted, they are perfecting their “role” in the play. You might literally see this, as they get on one knee and present perfect bow, like a prince. They become demure and debonair. Their drawings become very neat and precise, and they color within the lines. Their projects are done just so, and they say as much, “This piece is going to go exactly here.” Five year olds also have a personality and an exuberance that is of note. It is, indeed, much more perfected now. At four, we were worried that children might jump off a high place, pretending to be Superman. Now at five they are bopping their head to the beat of the music or dressing up as a sultry princess. To me, this is the charm of being five.

People say the most growth that children will ever go through is from when they are born until they are aged two. I disagree. I think the amount that children learn between the ages of five and six can rival, even dwarf, what they learn in the first two years of life. Age five really is like no other. At five, children aren’t four and they aren’t six. They’re five. They even go to a special school for it: kindergarten. It’s not preschool, but it’s not quite official “school” yet. Kindergarten is entirely its own thing, just as five year olds really are their own kind of special thing.

To say age five sees major memory upgrades is a giant understatement. First, it’s an upgrade in attention span (45 minutes or longer of concentrated effort). Then it’s a memory upgrade with how long ago they remember things (back to a year). Then, in the late fives, there is a memory upgrade allowing them to retain a massive amount of information, day to day, using the very conclusions they drew to solve problems later. In this, they quite literally develop a mind of their own. Indeed, if you were to ask me the one major change that takes place between the five and six, it’s that children can no longer be fooled. At the start of five, children believe just about anything you tell them. At the end of five, they question things and can spot lies. They go from being intellectually gullible to being intellectually formidable.

The process that they go through to make this transition truly is fascinating. The Jean Piaget experiments with 5-7 year olds, I find, are very relevant in explaining how this works. In these experiments, Piaget showed that if you pour water in one container into another that is a different shape, at five, children think the amount of water changed. My research shows that by age six or shortly after, children can see that the amount of water stays the same. In other words—they can’t be tricked!

The process that they go through to get to this point, which I outline in greater detail below, happens in stages. In their early fives, children spend a significant amount of time seeing how objects slide over one dimension only. For instance, they notice as they move towards or away from a light source, their shadow gets shorter or taller. This is a relationship over one dimension alone, height. I name an entire below hill after this, “One Dimension.” They then start to deal with two dimensions at once, such as how something can be bigger than another but another thing is further away. I name a hill after this as well, “Two Dimensions.” Eventually they can deal with two dimensions at once (they see them as separate for a while), as well as deal with three dimensions. Hence by age six they can see that the volume of water, something with three dimensions, stays the same as it is poured from one container to another. In going through all this, children develop a tremendous amount of knowledge. And it’s not just knowledge. It’s knowledge that they personally deduced, that is put in context, and stays with them. There is a bit more to it than this but this, the knowledge children personally have and which they personally deduced, I think is why they become so much more intellectually formidable by the time they are six.

Given all this, age five, as such, is a very reality-oriented age. This is what they are doing. They are figuring out how things operate in a 3-D environment, specifically as things move and slide about across dimensions. You’ll see this by the end of five. You’ll see, first of all, their interest in literal slides (or ramps, etc.) in their mid-fives. But you’ll also see how exact they want things to be. Children will note how your family sits in a square shape at dinner. In their vehicle, they are in the second row on the left. They are sizing up their 3-D environment in exacting detail. Five, as such, isn’t a terribly wild or daring time, although five year olds can be, as noted, prank-pulling punks. Fantasy does play a role in a five year old’s development, but much of it, as I will outline, seems related to coming to a more refined knowledge of the 3-D space around them and how the different variables across different dimensions work.

In their late fives, children become aware of the ambient environment, and they develop a self-awareness that they themselves are actually in that environment. Up until the end of five, children seem to think they can make themselves invisible by sheer will. When they become aware of the ambient environment—one that they are undeniably in—they enter a hill that I call “Moral Reasoning.” They can participate in discussions about rules or morals, and they develop a deep, sometimes heartfelt desire that everyone get along and be treated fairly.

This was a brief overview of the growth of a five year old. Five year olds are smooth little creatures with a lot going on inside. They have many memory upgrades, and the predominant skill I see forming at age five is their transition from intellectual gullibility to intellectual formidability. The growth of five year olds is otherwise best explained by the “hills” of child development I found in doing this child developmental research. A “hill” is kicked off by intense, wild imagination. Children go “up” into fantasy and back “down” to reality, which is why I call it a “hill.” There are less hills than milestones, so they offer a nice framework to describe the overall development of children. I let the description of these hills take over to give the details of growth at age five.

The Hills of Child Development

As noted, a “hill” of child development is when children go “up” into fantasy and then come back “down” to reality. I find each hill follows a semi-predictable pattern, with distinct sub-stages. Getting into the nuances of these sub-stages is not terribly important for now. In general, however, children seem to be initially gifted with some kind of image. This image seems to be gifted to them biologically, during sleep. In fact, I would say these sleep disruptions are the main cause of most “misbehavior” seen in children, where they have nightmares, stay up late at night, seem bothered, or overtaken by something. These images are totally wild at first. At five, children might see a moat on the floor or become obsessed with treasure or gold. It’s too reliably predictable across children to think that something other than biology is at work. These images, which manifest themselves into what we outwardly see as imagination, are reliably followed by an intensely curious stage. This is seen by adults as any of children’s famous “Why?” stages. This stage also seems to, in general, be a period of “misbehavior,” because children want to grab and touch things as they explore. They also want your attention a lot, as they ask their questions. As they investigate the world, they gain knowledge about it. With knowledge comes confidence. They start to build more creatively, just doing it to do it at first. They then get more aggressively creative in their surrounding environment, solving immediate problems. This is coming down the hill, as they practically apply their newly acquired skills. At the end of the hill tends to be both a heightened sense of realism and self-awareness. They explicitly are annoyed by their previous babyish thoughts. They also get hard on themselves as they reflect on who they are now. I call this the Refinement Stage.

I think it’s worth noting that the beginning of a hill almost always starts with sleep disruptions, nightmares, physical growth, new fears, and a huge memory upgrade. If you want to know if your child is starting a new hill, these are the things to look for. The memory upgrade at first is an upgrade in memory capacity. With an increase in memory capacity, children can remember things in more detail or longer, but they don’t have a lot of details memorized yet. As the hill progresses, their memory gets populated with data and details about what they find in their curious explorations. Fear is also present at the beginning of a hill. It is in fact as if this fear jolts them into paying more attention to the world around them. The fear is pretty quickly made up for by heroic thinking, in which they can slay these fears, if but in imagination. Their imaginations otherwise progress in complexity as the hill progresses. Their imaginations are wild and ineluctable at first, then they get more detailed, as children apply fantastical solutions to real problems. Their imaginations then become complex and detailed. Eventually it results in them personally applying their new imaginations and heroism to themselves. They personally are the hero, adopting a “role” as they go about slaying life. There is a notable absence of imagination at the end of a hill, in which there is almost this sense of jolting, pure realism, although hills tend to overlap. If you ever want to know where your child is on a hill, look at what kind of imagination they have. The more wild and seemingly delusional the imagination is, the closer you are to the beginning of a hill. The more control and more details they have in their imagination, the further along you are on a hill.

During any hill, the child is working on the same new core set of skills. A typical hill at age five lasts about three months but they come at a frequency of every two months. So, yes—they overlap quite a bit!

A Brief Overview of the Hills of Child Development of Children Aged Four

To understand where we are at with a child who is five, we need to recap what happened at four. Age four was all about self-awareness and growing day-to-day memory. Much of the development at four was children individuating themselves from other people. This starts for humans, as it usually does, by noticing something external, i.e., something about other people or things. In their early fours, children first begin to see the true personhood of other people—and they glamorize it. Four year olds are known for their love of superheroes. They become fascinated with the essence of other people. They then start to piece together who they are, as against the backdrop of their environment and as compared to other people. They also come to realize that you have your perception of the world and they have theirs, and these two things are not the same. Even something as simple as the fact that someone else can see something that they can’t, say a house while driving in a vehicle, rivets them. In other words, they individuate, i.e., they realize they have their own perceptions, and you have yours.

Life also becomes a continuous “reel” for four year olds. They remember what happened last week, they take reasonable guesses as to what will happen in the future, and they delight in knowing that they can do these things. For this reason, I would surmise, your earliest memories of day-to-day life are probably from when you were around four.

In this individuation of self and persistence of consciousness, four year olds come to realize that they, themselves, really exist. This is huge. With it eventually comes an intense fear of death, which is highly observable towards the end of age four. In through all of this, their individuation of self and understanding that they can somewhat predict future events, they start to realize that to work effectively with other humans, you have to plan and coordinate things. And this is where we left off, at age five. And age five is very much dominated by learning how to get along effectively with others. In fact, age five starts with a bang, with children intensely inserting themselves into the play of other children.

Here are the hills at age five. We left off at “Negotiation” from age four. (It is called “Short-Term Logistics” in my book Misbehavior is Growth: Four Year Olds. I decided to change the name to make it more relatable and recognizable.)

There is a lot of overlap in the hills at age five. This doesn’t necessarily mean age five is more difficult. It just means there is a lot of overlap between the misbehavior and the growth!

Here is a breakdown of the hills of child development at age five, i.e., the highest-level overview I could ever provide, while also having some number of meaningful details. The ages are listed in [year.month] or [year.month.week] format. Note, indeed, that some of the hills overlap.

Negotiation (4.11 – 5.2)

From their hard-earned knowledge from when they were four, children now realize that you have your own thoughts and they have theirs. They also understand that you can make somewhat robust plans about things in the future. Children are, at first, very uneasy that any of this will go well. They become supremely bossy in their early fives, to the point that it might present some of your biggest parenting challenges yet. Children become very bossy, wanting their sister to play with them or wanting things to go a particular way while out at dinner. Fear not—this is temporary. There are ways to handle this effectively. And your efforts will soon pay off. Children in their early fives soon become adorably polite, asking permission, and apologizing profusely for why they were late. Age five is, for many, truly a “golden” age.

Age five for children is otherwise quite simply marked by an increased use of their cognitive mind. They evaluate things cognitively before doing them. Even in their very early fives, children understand theories of how things ought to work, and they keep it with them, persistently, using it to make decisions. Think of them out there at a baseball game, knowing the rules of when they should go get the ball and when they shouldn’t. They can, in a simple form, do that kind of thing now.

There is also a strong increase in what can be considered a love hormone at age five. (I use “hormone” loosely. I don’t know the biological process that forms any of this. I don’t think any of us do.) By this, I mean children love to participate with other children to the point they might run around trying to kiss them. They also have a distinct personality to them. This sort of swag is seen even in the early fives. As children take over their own life more, they develop a heroic archetype. They personally are the hero, and there is a certain vibrancy to that. Even in the early fives, this heroic archetype has a bit more swag to it. They are a sultry princess, a pirate, or a cool kid who bops his head. This really is what being five is about.

Children’s attention span also increases at this hill. They stay with complicated games for 45 minutes or longer. This speaks to the intellectual fortitude they have, where they make decisions more with their mind. They actively think of new solutions and in a detailed way. Should we get a dog? Maybe, but we need a fence. They also start to negotiate—and well. Some make fun of this, as a little annoying quirk of kids, but personally I think we should feel so lucky that they are actively trying their hand at negotiating and making things go well. My research shows that five year olds genuinely want social situations to go well and be harmonious. By just 5.1 or 5.2, you will have a very polite child, who might, say, apologize profusely for holding you up, because they couldn’t get their shoe on, explaining exactly what happened.

One Dimension (5.1 – 5.5)

There is a sudden memory increase that kicks off this hill. Hills always start with sleep disruptions, fears, and a noticeable memory increase. Specifically, at the beginning of a hill, it is a memory capacity increase. This means they have the capacity to remember more, though they haven’t populated this memory with information yet. At this hill, they can impressively remember things long-term, back to an entire year. This is big.

At this hill, which starts around 5.1, children get really good at how things change over one dimension. They notice that as they pull their spoon away from their face, their reflection looks smaller. It’s specifically that they notice that a given input, [x], them moving the spoon, results in [y], their face looking smaller. They notice many other correlated relationships, as well.

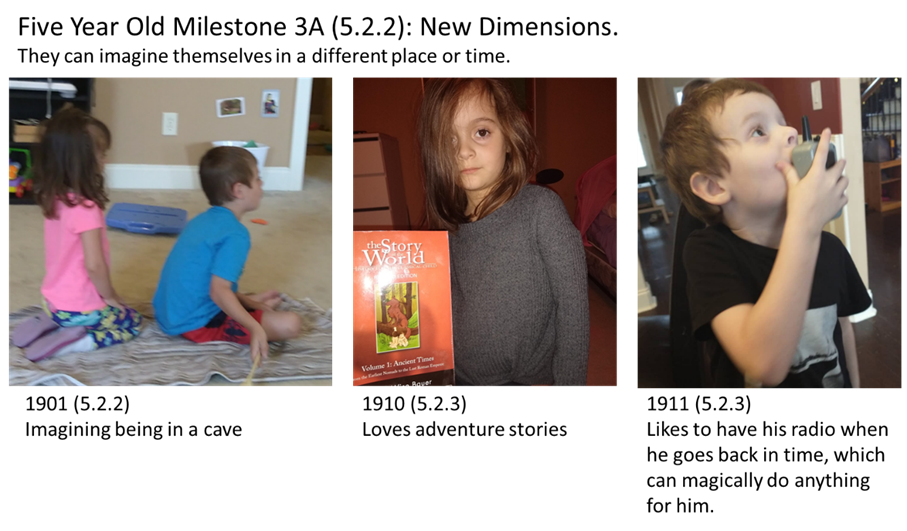

As the hill progresses, children start to imagine wild things about what will progress. They imagine they will keep getting so tall that they’ll bump their head into the ceiling. They can also literally imagine themselves in a new dimension, such as in a new place or time. They’ll love adventure or history stories around 5.2.2, as they imagine themselves going to a different place or time. My recommendation of what to do with five year olds is to read, read, and read some more to them!

At this hill, they also start to understand that two different dimensions exist, such as the height and width of something. However, they can’t deal with the two dimensions combined together yet. They can see that each dimension exists, but each dimension is separate in their mind. To see this in your child, try the following experiment. Put water in bowls of two different widths and fill them to the same height. Ask your child which has more water. They will likely say that each bowl has the same amount. This is, as I am but surmising, because the bowls are filled to the same height, and they are spinning off of height (one dimension) alone. However, they might also very well note that one bowl is wider than the other. They quite simply see only one dimension at a time for now.

At this hill, in which the child’s memory gets populated with the correlated relationships they are noticing, there is an increase in working memory as well. They were blessed with the ability to recall memories from the long past (back to a year). Now they can draw conclusions, and those conclusions stick in their mind over the long-term now. They draw a conclusion that their dad must have taken the car other than the one on the driveway, and they casually mention it hours later. Their working memory becomes truly impressive, perhaps drawing a machine they remembered from a movie with great detail, on the spot, without having to look at the machine. They can also work on their projects for hours now—as many as nine! I also found that things I taught my children at this age they surprisingly remembered years later, even totally obscure things, such as the stalactite we showed them at a cave once.

Children also develop a further sense of heroism and drama at this hill. I described that at age five it’s as if they are perfecting their role in a play, and you literally see that in this hill. They step up to chop mushrooms and they do it with the flair of a master chef. Five year olds are smooth. They also love deep and moving things, such as a song meant to inspire soldiers to go into battle.

As a hill rounds out, children get more proactive in their environment. They initiate new games, want to do new plays, and do new projects. This passes quickly into taking initiative in the immediate environment as problems arise, such as flagging down a waitress to refill their drink, which they do spontaneously, entire on their own initiative. Maybe this is a result of their new awareness of correlated relationships? Afterall, if they want their drink refilled, shouldn’t they ask the waitress to do it? They become more judgmental as well, perhaps saying things “suck.” It seems as if having more knowledge like this, knowledge that they personally concluded too, makes them more judgmental of things and less willing to just accept what people say.

By the very end of this hill, they also become yet more self-aware, realizing that playing an odd professor in fact makes them look odd. This heightened self-awareness is usually the sign that a hill is ending and a new one is beginning.

Two Dimensions (5.4.0 – 5.7.0)

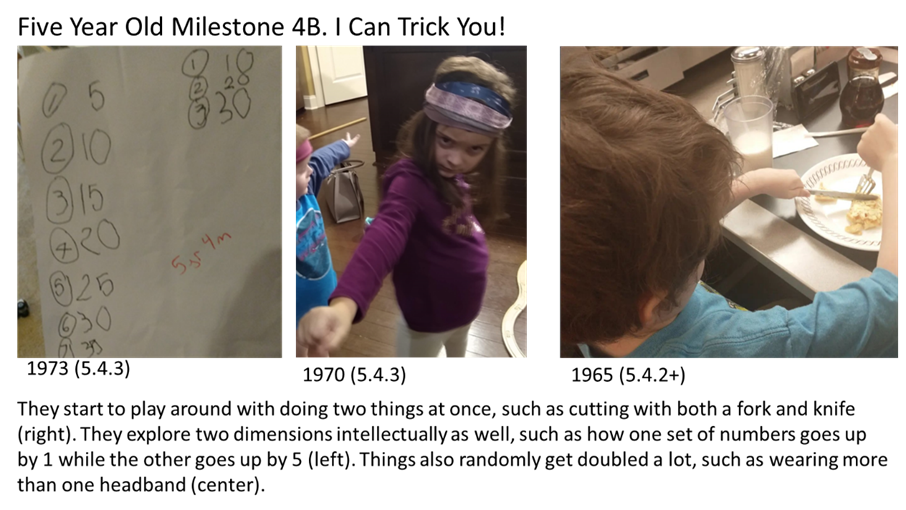

This hill probably starts out subtly when children spontaneously notice that eating food will make them “both taller AND wider!” which is around 5.4. But, in order to truly understand that things have two dimensions that make them up, true to my research, children need to play around with the idea. This starts more noticeably around 5.4.2.

My research shows that wild imagination kicks off major new mental development. I believe what kicks that off for this hill is when children believe imaginary things external to them can do powerful work for them. For example, they imagine that invisible computers that they communicate with can grant their requests. The things they imagine often have two dimensions that make them up, which they note. The computers are long and wide or short and tall, they tell you. This type of imaginary thinking seems to kick off curiosity for them, to investigate something about reality.

As noted, children seem to need to experiment with things before understanding them. The curiosity is there, gifted biologically, but they need to get their hands on things to understand them. At this hill, they are starting to understand how two dimensions make things up. They might start to play around with this by doing two things at once, such as cutting something with both a fork and a knife. (That humans can deal with 2- or 3- dimensions well and have two hands, which we can bring to our face to examine things, is no coincidence, in my opinion.) At this hill, children also seem to be unable to help but combine things. If they see two words, these words get combined together, as do symbols, numbers, and more. This will also affect how they solve math problems, as they randomly double numbers that shouldn’t be doubled. They also cut things in half, and each half of what they cut might take on a life of its own, as they make up a story about it. Everything is “2” for them for a bit. They explore specifically that things can be in two totally different dimensions. A queen could be the queen of a city named Queens! One is the title of a person—the other a city! Isn’t that neat? It results in them being able to hold onto to two totally different dimensions at once. They can accept that something is bigger than another, but another is further away. They can hold onto these things, mentally, at the same time.

I note in some of the milestones on my website (www.theobservantmom.com) that children become interested in squares or symbols and such. Some people find this highly specific observation odd. Let me explain. To understand anything new, children really break things up into building blocks. That children draw people as stick figures is a testament to this. They break up the essence of a person into a circle for the head, a line for the body, etc. This is essentially how they build an understanding of the 3-D world too. These building blocks appear to serve as sort of place holders, a mental hook, as they build a more refined knowledge set. At this hill, symbols, shapes, and words seem to “pop out” at children. To see how children see things as “squares,” one of the Piaget experiments can show how children need things to be in a square or rectangle shape. To do it, put two rows of three of anything, such as coins, in front of the child. Space the three objects equally apart. Ask them which row has more coins. They will likely get the answer right: they are equal. Now spread the coins in one of the rows further apart. Now ask which has more coins. They are likely to get it wrong. They might say the wider one has more coins, or they might even say that the shorter line has more coins. From my observations of children, it’s as if the extended coins go into their peripheral vision, as if anything but a square or rectangular shape confuses them.

So, this is why I note that children at this age seem to take an interest in certain shapes, especially ones with two dimensions, such as squares. It seems to be an important development. It might even cause problems for parents. If things aren’t in a perfect square shape, such as how your family is arranged when sitting at a dinner table, children at this age can get upset. And all of this, where they “see” symbols everywhere, again, speaks to how children seem to be gifted with “images,” as my work finds, which kicks off a hill, which then drives their mental development.

At the successful completion of this hill, children can not only understand but use two dimensions at once. They can do one of those logic puzzles where you have to fill in a letter based on what column and row it would be in, i.e., they use two dimensions at once. They see that one solution works in one context and another solution works better in a different context. They, as such, can explain exactly why one solution works, e.g., they directly verbalize, “To build a tall tower, I need a wide base.” As the hill rounds out, they impressively apply this, even doing some engineering in their free play, perhaps figuring out how to make sure people who slide down a slide have a soft landing.

At the end of this hill, children can also pursue goals they have more persistently. It’s as if they can understand they are in one state, as a beginner, and they want to persist at getting to another state, as an expert. These are, after all, two different dimensions, and ones they want to traverse. They, as such, develop much more tenacity. They can stick with things longer, wanting to win.

At the end of this hill, they also no longer think that things can grow forever, such that they will someday bump their head into the ceiling if they keep growing. This sense of new realism is typically a sign of a hill rounding out.

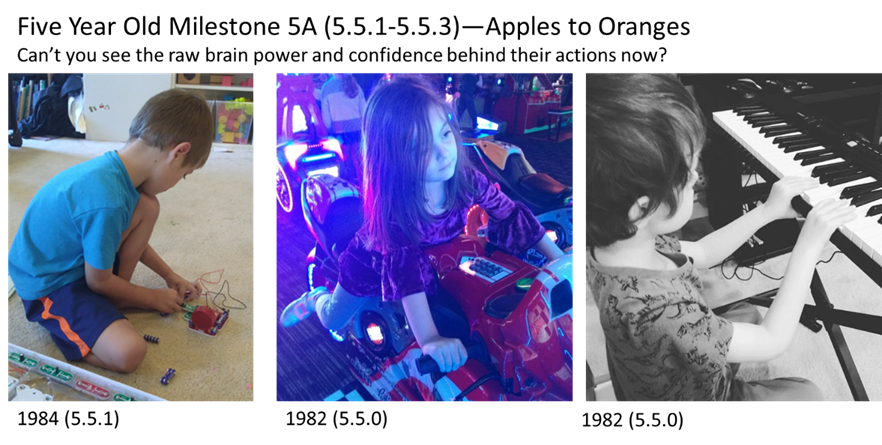

Intellectual Formidability (5.5.0 – 5.8.0)

In being able to hold onto to two dimensions at once, children appear to develop a database of knowledge that now lets them evaluate the world more realistically. They have an enormous working memory, with many correlated relationships that they’ve noticed, and stored off in memory. This means they have an idea of what is realistic as far as what, when, where, and why things happen. They have an idea of context. You wear coats outside, not inside. There are two dimensions to deal with here 1) the fact that someone is wearing a coat and 2) the fact that they are inside or outside. Having some hard-earned experience, they know which of these situations makes sense and which does not. This makes them far more intellectually formidable, i.e., far less easy to fool. When they see a video in which it is raining inside, they say, “Hold up. That doesn’t make sense.” This is the essence of this hill, Intellectual Formidability.

I believe this hill starts around 5.5.0, when children start to fantasize about attaining treasure. This simple, singular desire is the type of wishful thinking that kicks off a hill. It then transpires into them imagining that something external will provide power to them, such as they might pray and get their prayers answered. At this hill, they also talk about how their brain operates. They have a conscious understanding that their brain controls their body. They similarly imagine they get gold or that something external will give them something—these are powerful things. I think this all speaks to the new intellectual formidability they show at this milestone.

Although I named this hill Intellectual Formidability, what drives this new notable skill, I believe, is an interest in resolving differences in perception. This probably starts, indeed around 5.5.0, when children notice two people can see the gate to a fence as open or closed, depending on the angle they view it. But noticing how there can be errors in people’s perception of things is what drives this hill. Using the hand gestures of a professor, some children can explain how some people were wrong when they thought the sun revolved around the earth. They really, really want to make sure that you understand the issue at hand and that you both are on the same page. This happens more noticeably around 5.7.0. At this age, they might also start to tell imaginative stories that involve two characters having a different perception of something, possibly causing problems for each. They also like to think about what life would be like if you were something else, such as an animal, which is also a sort of difference in perception.

In noticing that people can see things differently, children can start to wade issues of what is real or fake, who is lying, or what are understandable errors in perception. They can impressively identify if someone is lying. They can also see what is fake or real. Cinderella is so FAKE. Julius Caesar actually existed. He is REAL. They cannot easily be tricked or lied to anymore, which again is that intellectual formidability seen at this hill. No longer will they accept things just because they are told so. They also start to want proof. How could people possibly have learned what organs are inside the human body? How does Santa get into your house if you don’t have a chimney? They wonder about things like this now.

Their ability to not just understand two totally different dimensions but to use them both at once starts to grow more at this milestone. Before, for a period of time anyways, two dimensions were split. They looked at height or width. You can either go to Restaurant A or B, not both. Now, two attributes or actions can coexist. A balloon can impressively be both light and big. They also even move into a world of three dimensions, where they can intellectually handle three attributes at once. They can ponder how many points a cube (a 3-D object) has. They can handle that something has three attributes: someone can be funny, sad, and angry at the same time. Their projects literally get bigger, where they want to make things that are impressively tall, with many interesting details. They can start to handle numbers in numbers, details within details. This sets them up nicely for the next hill, where they have loads of theories in their mind and start to tie them to the reality around them, with impressive detail.

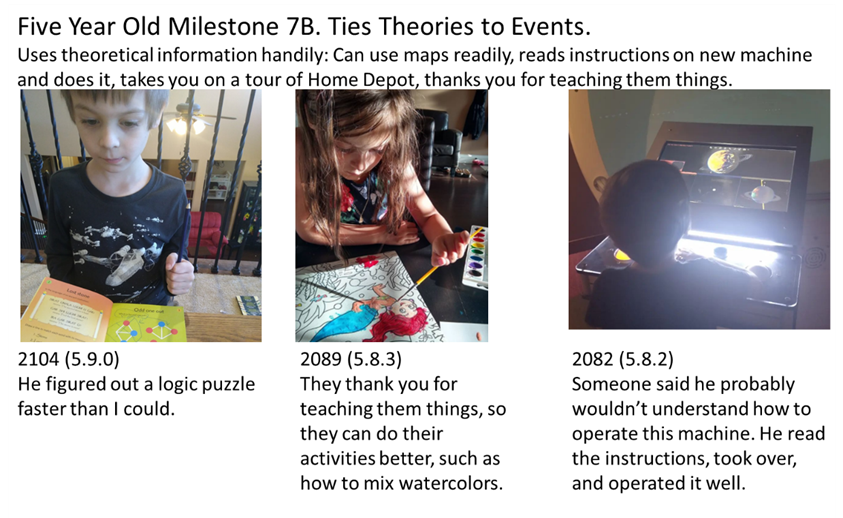

Theoretical Reasoning (5.8.0 – 5.10.0)

They have incredible conceptual information at this hill, and they use it to navigate life. They can, for instance, readily absorb any new map presented to them just then. They figure out that you have yet to be to that one spot on the map. They can pore over the entire periodic table of elements, holding on to information about each element. They can go between theory and event easily. They hear of a theory, say that the earth is round, and x, y, z is proof. When they see it live, they note it. They can do math on the spot, say at a grocery store to figure a figure a few things out. They can apply ideas to practical problems, such as actively participating in family meetings where you brainstorm solutions to problems. They get better at using strategy when playing board games. They can also come up with a solution to a life problem, such as how to catch a mouse in your house. In short, they take theories and apply them.

This hill probably starts around 5.8.0, when they start to have sleep issues and love to watch or read things that offer them an enormous amount of information. They bubble about being able to watch TV or videos and how much it teaches them. However, this hill really takes off around 5.9.0, when they tie theories to events and use conceptual information masterfully. Imaginary friends might make a new appearance around 5.9.0, and they also have nightmares. They also physically grow and there is a brand new intense, aggressive energy that is of note. They really want to be invited to “the party” now. These are all signs that something majorly new is brewing.

At the end of this hill, not only do they accept that two dimensions exist, they notice nuance between them. Something can look cheap but not be cheap. You might want to get out of a place quickly but quietly. They truly have a lot of information in their mind. They impressively not only remember things day after day, but they notice patterns about what happens day after day. Their mind is like a wheel that was loaded up with information then set at high speed to just turn rapidly. They hold on to not just information but competing information and they do it rather masterfully.

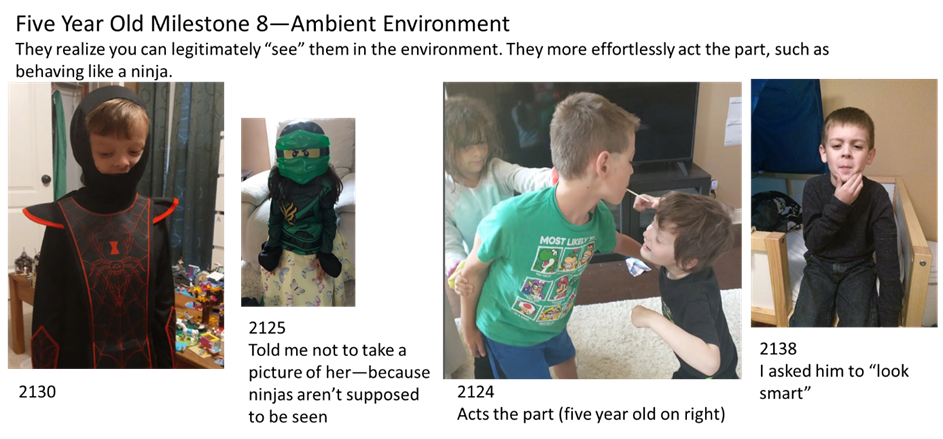

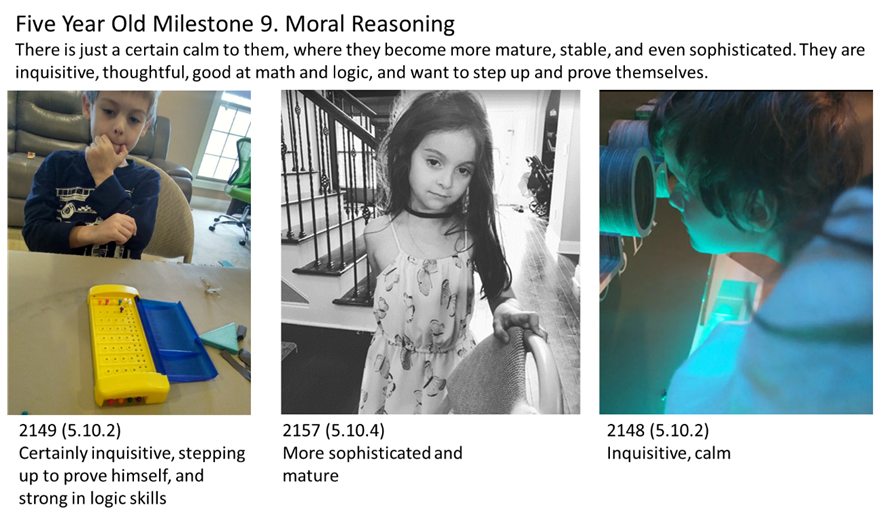

Moral Reasoning (5.9.0 – 6.0.0)

At this hill, children become interested in the rules that govern human relationships. They become highly interested in the rules or morals that govern this outer world. Do they have to obey rules even if those rules are cruel? They can compare not just two different objects but two different sets of rules. They can see the differences between the book and the movie. They can also impressively get the moral of the story of any book or movie, e.g., about Willy Wonka & The Chocolate Factory, they note, “Charlie was good. He gave the candy back.” Note that some children might be into the “rules” of the outer environment while others more into the “vibe” of it. But how they fit in with their outer environment is of big concern to them at this hill. At the end of this hill, children really want things to go well for everyone involved. They don’t just want to make sure they get their turn, they want to make sure their brother gets his turn, too.

At this hill, children also realize that other people can legitimately “see” them. Before, they seemed to believe they could become sort of invisible at will, or, at least, could trick you that they are invisible. Now they really realize that others cannot be tricked; others really can see them. They realize the environment as a whole and that they are part of it, almost like they realize they are also a chess piece in the chess game of life.

This hill probably starts around 5.9.0, when children like the thought of “talismans” doing powerful things for them. This might be a shark tooth necklace that makes them feel powerful or fantasizing about a genie giving them three wishes. The wishful, heroic thinking starts off a hill, as does physical growth, fears, and sleep disruptions, which are also seen around 5.9.0. But the actual growth in this hill is not seen until around 5.10.0.

There is an impressive increase in memory at this hill. They can keep up with the same string of information day after day. They can, for instance, listen to a chapter book day after day and remember what they read the day prior. As the hill progresses, they can notice patterns of what they notice over time. Their sister is getting less bossy as she gets older, but she’s still a bit awkward. They also can willfully decide what memories they keep or not. At the very end of this hill or perhaps at the beginning of the next one, they might say they are willfully pushing something out of their mind that they don’t want to think about it. This strikes me as big.

At this hill, true to what one might think of when they think of a child becoming a more “moral” being, children become much more mature and demure. They don’t run all over pretending to be The Gingerbread man, the famous cookie who escaped from a hot oven, anymore. They sit and listen to the story, noting that The Gingerbread is acting a bit dumb. They also pose nicely for photos. They don’t turn around and show you their butt at the last second anymore.

Children really are different by the end of this hill. They make decisions entirely on their own, they are very exuberant and present in their environment, they get the jokes people tell, they play the games, understand the strategies, and they banter back and forth. They become more like what they are like at six, which is less of the calm, here-and-now child you see at five and more of a freewheeling, in-your-face punk.

Probably and Ratios (5.10.0 – 6.0.0+)

Up until this last hill for age five, children have been grappling with theories, yes, but most of them applied to the real-world in a concrete way. They’ve been examining fundamentals of reality itself, such as how objects have one-dimension, then two, and then how two dimensions relate to the other. They’ve still been fairly imaginative up to now, even seemingly believing their imaginations, such as they have fake food in their pocket. Now, at 6, most of that is shed. All of this has been building a very formidable, realistic mind that has its own thoughts and judgments.

At this hill, they enter the world of the theoretical, but it’s yet more abstract. They can handle the idea of things or concepts that they cannot personally see in the here and now. They start to understand probability, such as, “Someone else probably has my name.” They can, if taught it, deal with negative numbers—something you can never really “see.” They can do impressive open-ended logic such as, “Name an ocean that is not the biggest.” They deal with things that are not here, right now, but they can theorize about. As this hill progresses, which is into age 6, which is somewhat outside the scope of this analysis, they understand ratios. They can understand that if the ratio is 1:2 apples to oranges that 2 apples would mean 4 oranges. I would describe the entire development over age five as learning to deal with two totally different dimensions at once. And now they can deal with 2 dimensions almost entirely abstractly, and how one increases as the other does, which is what a ratio is. That is impressive.

This hill probably starts around 5.10, when they become scatter-brained. They also get confused about abstract representations meant to be symbolic, confusing them as real. A cartoon rocket in a video meant only to show how big a crater on the moon is gets confused by them as a real rocket that someone put on the moon. They are about to deal with highly theoretical things, what is probable even though you can’t see it, and this perhaps starts with confusion about what is meant to be a mere symbol. You start to see the skills around 5.11.0 and more so after 6.0.0.

And, as for the big new skill seen, they understand conservation at this hill. This is what I described in the introduction to this article, and what Jean Piaget took an interest in. Conservation means they can see that the volume of something stays the same regardless of what container it’s in. So, if you take water from one tall container and pour it into a wide container, the amount of water stays the same. I believe I may have described the mechanism by which this forms, from age 5 until now, which is about age 6, as contained in the hills previously described.

To recap, my research shows that to get to this point, where children understand the volume of water stays the same even if it’s in a different container, children need to play around and theorize about the 3-D world itself, specifically how things change over any given variable. They do this in steps. First, they examine things as they traverse over one dimension alone. They do this when they notice, “Oh, when I walk away from a light, my shadow gets taller!” At first, they can only “see” things as they move over one dimension. As such, when the same amount of water is poured into two different-shaped containers, all they can see is height, i.e., they can only see one dimension. They can’t see height and width. As such, to them, whichever shows the water filled to a higher height will have “more” water. Once they master relationships as they happen over one dimension, they move on to two dimensions, and then three, as well as how two or more dimensions can interact. At each stage, they are noticing relationships, of which they deduce themselves. They might be “wrong” in the conclusions they draw, but given the data they have, they actually aren’t wrong. (And wrong information from adults can also greatly color their conclusions). But, by the end of five, they can see that the amount of water, its volume, something that has three dimensions, stays the same as it is poured from one container to another.

I want to add also, as they develop these skills, I think it’s important to note that they notice many correlated relationships in the dimension(s) they take an interest in, which they categorize and tie off, mentally. I think that this—categorization—is integral to human memory. In other words, they (and we) don’t just memorize a long list of things. They group them, for instance, by grouping a certain group of songs as belonging to a particular band. They have many correlations categorized in one dimension before they move on to two dimensions, etc.

Another important development at this hill, relevant again to their new skill of understanding conservation, is that they develop willful control over their thoughts. By 6, children can actively push out of their mind what they don’t want to think about. This seems big to me and relevant to this new skill of conservation. Indeed, when I did the Piaget experiments with my children around age 6, they all asked me a question, “Are you asking me how many more coins there are or which row is longer?” Things don’t just “seep” into a child’s anymore. They ask questions and have active, willful control over their thoughts and the answers they give. A rational, formidable mind has truly formed.

In order to get to this point, at six, the final hoorah of the development of age five, they have had to notice many correlated relationships and stored them off, mentally. They have not just knowledge but knowledge that they personally deduced. And the knowledge they have is not just knowledge but knowledge in context. This makes sense, that doesn’t. They can handle information as compared to the situation it is in, handling multiple moving parts. I believe this is why you can’t trick children by the end of five. It’s the massive amount of knowledge they have, knowledge of which they personally deduced, and which is now in context. This all perhaps seems technical, but it’s important! Any of this might cause issues as well. You might understand why it’s so important to your five year old that you sit in a perfect square at dinner. Major mental growth is happening! Brain under construction!

And this takes us to age six. Six year olds are bossy. They are fiercely independent and they’ll take “justice” into their hands. But, alas, that is for a different blog.

Top three educational activities for five year olds

These are the top three educational activities that I would do with any five year old that I was charged with.

1. Read adventure stories

If there is one thing that I encourage you to do with five year olds, it’s read to them. And I encourage you to read more complex things at even younger ages than you might think possible. All throughout child development, children change very suddenly. They experience one such sudden change around 5.2.2. They can now imagine themselves in a different time or place. You should be able to notice this in children, as they talk about going through portals or into caves or such. At any rate, I encourage you to read an adventure or history story to them.

The history series I read to my children was Story of the World by Susan Wise Bauer. I recommend you go straight to Chapter One and start reading. It starts off with a child being tasked with finding a lizard so their mother can cook it later. This kind of thing enchants children. You might find children lose interest in reading a history series throughout age five, but I find they might want to come back to it at around age six or just before. At that age, I would add more to this lesson, such as putting up a timeline. For now, just go to new lands—exciting!

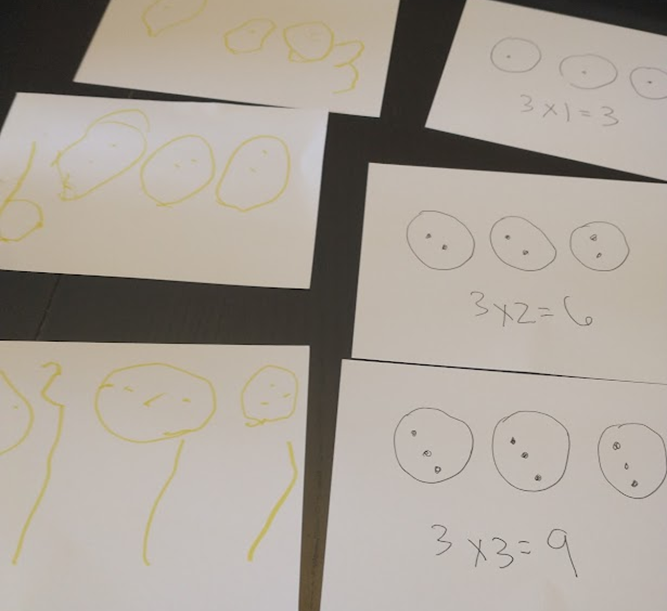

2. Play math

People tend to eschew a lot of academic work with young children. I want to emphasize here that I am not advocating doing traditional math with pencil-and-paper worksheets with endless equations. I am advocating to play math. I will forever hammer that traditional education goes too quickly to what I call “analytics.” They want children to read by decoding letters; they want to teach physics with equations on a chalkboard with little hands-on experience; they want to make children write with proper grammar before they have really formed their own thoughts. In math, they want children to manipulate numbers before children develop number sense—which is why math games are so powerful. If you want, you can think of it a bit like playing with the Montessori pink cubes, as to gain an intuitive sense of size, before telling a child “This is big” and “This is small.” I think you can start playing many math games with children around 5.6.0—basically 5-1/2.

A great series to find many math games that you can customize for your unique child is Denise Gaskin’s “Math You Can Play” series. You might start with her Addition and Subtraction book. One of my favorite activities to do with a child at this age, however, I found in her Multiplication and Fractions book, which I modified. I call it “Pizza Math.” In this, you draw a certain number of pizzas with a certain number of pepperonis on them.

I start with two pizzas with two pepperonis. Then you add up the pepperoni. In this case, there are four. Now draw three pizzas with two pepperonis on them and add up the pepperonis. I go up to five or six pizzas, depending on a child’s interest. Then the next day, we draw pizzas with three pepperonis in them. Then the next day, four. Again, I only go up to five or six pizzas with five or six pepperonis. This is a lesson in multiplication but I found it’s a great lesson or addition. When you draw four pizzas with, say, two pepperonis each, you see easily that 4 + 4 is 8. My children greatly enjoyed doing this with me, over the course of a few days. I would recommend doing this around 5.9 or 5.10.

In general, learning math comes down to breaking up numbers and putting them back together. Many math games can do this, as can verbally going over math with your child. Children show an intense interest in math around 5.6.0. When they start to wonder what 8 + 5 is, ask them what 8 + 2 + 3 is. Many math games also work on breaking up numbers like this, such as the “Shut the Box” game, which you can buy commercially. I also made liberal use of number lines with children, which give an intuitive sense of numbers.

3. Read a chapter book

I insist you do this. At around 5.10 [years.months], children can keep up with a book that you read day after day. I insist you pick at least one chapter book that you think you can totally finish within a span of 2-4 days and read it to them. Set aside some time for this special accomplishment. Pick an adventure book with exciting heroes. When you finish the book, it will make your child feel big and important that they finished a whole book.

As far as what book, Wizard of Oz is my go-to. Frank L. Baum intended this to be a new sort of children’s book that enchanted children. After you read it, watch the movie. Children in their late fives can remember the themes and details of the book and the movie and notice those differences. Other books that might also work are “The Great Classics,” or something similar, which condense classics down to about 20-25 short chapters.

Parenting strategies for five year olds

So, I know it sounds cliché, but giving children plenty of instruction and guidance really works well, especially at age five. Five year olds show genuine confusion over knowing what is right or wrong, and they want to work hard to do what’s right. Give them ample information about what to do and how to get what they want. If they want to get their sibling to play with them, offer clear guidance on how they might do that. If you are going to a restaurant, give a clear run-down of what is going to happen, how you will pick who gets what seat, etc.

Five year olds are also very exact and specific. If you want them to do anything, laying out materials nicely will help. Let’s say you want them to get dressed on their own. Having the clothes organized nicely or even laid out will help them. Make sure they know where things are and what’s going to happen.

Five year olds have a lot of irrational fears. They are worried they’ll grow so tall they’ll bump into the ceiling or that they’ll die on a Tuesday. They are also now worried not just that they’ll die but that you will die. One remedy to this, one most probably take for granted, is to put them in touch with their grandparents. In doing this, you show them humans live for a long time and, at any rate, while it might be morbid, the first person likely to die is not their own parents but indeed a grandparent. I have found children not in touch with their grandparents show greater instability and fear over their parents dying. Some even explicitly point out that the oldest in their family, perhaps a parent, will be the next one to die. If grandparents are not around, perhaps tell them about their grandparents, emphasizing how long they have lived so far or how they lived to an older age.

Another somewhat unconventional but, I find, effective, way to settle children’s fears is to give them a toy that they can infinitely play with, even try to break, showing them that they can’t. A toy doll made out of rubber can do this. They can stretch this to their heart’s content—but it will never stretch so far as to break through ceilings or walls. An old-fashioned “Popple” toy, which is a stuffed animal that can roll into a ball, is another example of a toy that can be infinitely played with. When I go to children’s toy shops, I see this kind of toy is still popular—and I think for a reason. I suspect it will frustrate children that they can’t ultimately break the toy, but based on my observations, something becomes very settled in them as they try to but can’t break a toy like this. It sets a certain object constancy into place. Children might benefit from this around 5.6.0 or a bit before. This will also give some of their more “violent” tendencies, which are seen at 5-1/2, an outlet.

Otherwise, to get to the bottom of their fears, you might indulge some of their fantasies. As they are telling you about traveling through portals or to caves, ask them questions about it. After, in and around this, they might open up to you about what they are thinking. Then, simply assuring them that their wild fears will never materialize might help them calm down.

Children also physically grow a lot at 5. They, as such, might get hungrier. If you are getting, “Is it done yet?” treatment about food, you might consider increasing how much food you offer them.

Another thing about five year olds is to not underestimate them! They might surprise you with what they can accomplish, perhaps trying their hand at a 300-piece jigsaw puzzle. If you deny them this opportunity, it can cause unnecessary frustration, just to find out later that they were very well capable of this impressive accomplishment. Giving them just a bit of instruction when they get ambitious like this can also go a long way.

In the late fives, children can get aggressive, even menacing. They purposely antagonize others and also seem to purposely bring distress upon themselves. Matching their emotions can help. “I see how very important this is to you.” They may or may not then do the “right” thing, but it will calm them down. I found I sometimes just had to be forceful with children. If they took another child’s toy, after calming them down as best I could, I would simply take the toy back. Then, distract them somehow by getting them to do something else.

Otherwise, be prepared for some of the irrational thoughts and fears. They might think that going to one store means you cannot then go to another store, as you promised them. You might just have to validate the feeling for now and endure some of the tears. They might also get upset that you all are not in a perfect square as you play pass with a soccer ball. These are quite simply the things that are important to five-year-old children.

I never tried it when my children were five but one idea I have for five year olds is to develop rituals for them. I read about rituals in Arnold van Gennep’s classic Rites de Passage. Rituals have been developed all across the world to help people as they transition in and out of social groups. The rituals involve separation, inclusion, and the transition between. This could be, for example, engagement and then marriage. This involves separation from one’s birth family, inclusion into a new family, and there is a transition in between, the engagement. Well, being five is all about attempts by the child to be included in social groups. Perhaps a proactive attempt to bring them into the group would settle down much aggressive behavior. I didn’t have the privilege to try this when any of my children were five. However, I did employ it at older ages, especially when my children joined a new club or organization. I gave it a ritualistic feel. We marked the first day that we were to do anything with the organization on the calendar. We counted down to it. I explained exactly what would happen. We talked about how great they would do. It did help.

I was most fascinated to learn, from reading Gennep’s book, that young children in some cultures were given statues of women, to act as a “mother” watching over them and loving them. I found this, verbatim, with one of my children when they were 5. He wanted a picture of a woman, which was the stock photo inside a picture frame. We later found out he wanted “another mommy.” You might consider this when children are 5. Pictures of other “mommies,” perhaps their own grandmother, aunt, etc., might be deeply meaningful to them.

And, finally, here is me up on my pulpit and writing a bit off-the-cuff. I believe, in general, that children need ample instruction, guidance, attention, and, yes, even planned activities. I am a bit opposed to letting children experience “natural consequences.” The only real consequence to this, I find, is children feel abandoned. Children don’t have the constituency to deal with the “consequences” to their often forgetful or even “irrational” actions yet. They need you to set the example for them. My child development work finds that the development of human consciousness is largely collective by nature. In other words, children need you to see the same things they do for them to truly “see” them. They need you to especially see them, themselves. Children by nature are very limited in their perceptions. In fact, they are outright “irrational” in the things they initially believe. It seems to be designed this way. They have wild imaginations which serve one purpose and one purpose only, which is to spur curiosity. After this, they go out and get valid knowledge. In this, they need you, constantly. They need you to constantly point out new things to them, raise their awareness about things they didn’t see, give them new things to do, help them when they forget something, etc. In short, children need a “tuning fork.” Children catch your “vibe” easily. A vibe of patience, guidance, and generosity goes a long way with children. Children, in general, need more, not less. They need more activities, more guidance, more opportunities, more family, more friends. The idea behind Misbehavior is Growth is that children’s demanding behavior is an instinctual call on their part for mentorship from adults. I’m here to say: give it to them. I am, frankly, completely tired of and rather appalled by the proud stoicism and stinginess advocated by just about all modern parenting paradigms (dressed up in nicer clothing than this), which is essentially the same old, same old that’s been happening for centuries. It’s time to put children first.

Amber documents the age-related “stages” that children go through. Her book series is Misbehavior is Growth. Send your friends and family to The Observant Mom.