The trajectory of parenting approaches, over time, is towards less punitive measures against the child and towards extending them more respect and freedom. It is well documented that fewer and fewer percentages of parents support spanking, something that has dramatically decreased even in the last 30 years. Now, in 2018, it’s common to hear parents even say not to use “time out” in a punitive way. Time outs are so early 2000s. Time outs are on their way out. People are flocking to gentle parenting.

Yet even among gentle parents there are still remnants of coercive and unnecessarily limiting parenting. That is what I want to address in this article. There are two major typical popular thoughts that are unnecessarily limiting 1) that children “need” boundaries from loving and wiser adults and 2) to “ignore” their stages while “holding space” in effect letting them suffer through big emotions on their own, instead of going to the child to see what is going on (hint: amazing things are happening).

There is much thought on the market today about the potential of children. Any time a parent focuses too much on the seemingly ill behavior of a child, they are missing the bigger picture: the amazing potential of children. Underneath much of children’s bizarre behavior is a latent thought or ability. It’s getting to that potential, the underlying, unseen world going on inside our children, that is so vital. Here is a diagram showing this:

My challenge to the two common parenting approaches listed above is largely rooted in my work on child development. I have been documenting the “stages” that children go through: the age-related time when children notoriously become difficult. During any given stage, a developmental milestone, they might become whiny, clumsy, aggressive, or a host of other behaviors typically frowned upon by society and/or are frustrating to parents. My work has been documenting this ill behavior and what new abilities seem to come with these new stages, with the thought that each one is the child’s mind in the process of upgrading and during which the child goes bonkers for a period of time. I can directly challenge the idea that children “need” boundaries based on the very typical examples given where parents know “better” based on my work. In each case, the supposedly wiser parent is actually overriding what is natural and necessary child development. And it is one of my main goals of this work to challenge the idea that we should “ignore” stages, which typically means to not punish the misbehavior (which I applaud) but unfortunately also has a parent turning a cold shoulder to a child in need.

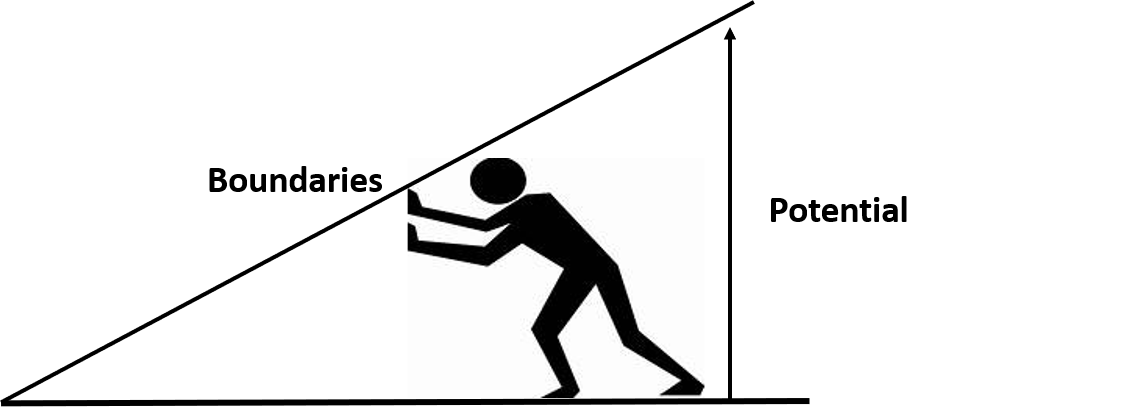

I am about to dissect very typical scenarios in which parenting experts suggest parents override their children’s seeming whims. Before I do that, I want to just linger on the idea that children “need” boundaries. I want to compare this idea that they need boundaries–something that limits their behavior–versus the idea, which parenting experts also share, to unleash children’s potential. Boundaries. Potential. Boundaries. Potential. Boundaries. Potential. They don’t jive. It’s the idea that children need them that I take such issue with, as if it is necessary to keep a check on the stuff going on inside of them for their own good. I can agree that sometimes you have to limit a child’s behavior, but it’s not for the sake of the child’s own internal growth. The child’s internal growth needs acceptance and freedom.

Typical parenting thought is that children need an “alpha parent,” someone who conveys they are in charge. For the most part, I don’t mind what is meant by “alpha parent.” It primarily means to take on a responsible caregiving role: anticipate they need food before they get overly hungry, be the calm when children are a storm, etc. But there just has to be a better word to describe this than “alpha.” Alpha implies dominance and, unfortunately, this idea of being “alpha” does spill over into unnecessarily limiting children’s behavior.

Here is one example of when a supposedly wiser adult should override what the child wants: when the child doesn’t want to go to sleep. This is from Rest, Play, Grow by Dr. Deborah MacNamara:

What is imperative is that adults don’t fall short of their responsibility to present life’s futilities, which are many, such as helping a three-year-old get to sleep when they claim, “I don’t want to go to bed. I’m nocturnal like my hamster.”

My work shows that during the developmental stages, children typically want to stay up later. I can tell my son in particular is in a developmental milestone because he always wants to stay up later. It only lasts a few days. It’s been like this since he was 2 (and is still going strong at 6). I have learned to let him stay up late. When his brain upgrades, he has a deep need to be near me, to talk, and to do new things. Stunning things have come out of his mouth late at night. New skills reveal themselves at these tender hours: one time he colored and colored and colored (3 1/2), another time he wanted to take flashlights and investigate a new house being built (4 1/2), another time he went on and on about the good and bad traits of his sister (5 1/2). I gained great insight into the new developments in his mind during these late nights. I see these late nights as times that my children need me and in which I’ll get great insight into their new abilities. I definitely do not see it as I am wiser and should enforce that they goes to bed (in some loving way of course). My children’s internal drive is much wiser than me when it comes to their development.

Here is another way in which MacNamara advocates we set a loving boundary and again revolves around getting children to understand “life’s futilities”: seeing to it that they learn to lose a game:

One parent was aghast at my suggestion that young children shouldn’t always win. She asked, “Are you saying I shouldn’t let my five-year-old win at chess each time we play? He’s just little.” I responded by asking her where she thought it best her child learn about not being the winner all the time. She contemplated this question and conceded that perhaps she did have a role to play in preparing her son for losing on the playground at school.

My work shows that being extremely sore about losing a game is highly age related. They go through a very long period in which they have a strong desire to always win and hate to lose. It starts at Preschool Milestone 13 at 3 years, 10 months. It lasts until at least 6 years old, although it gets somewhat better from then until 6 or maybe a bit earlier than 6 (and sometimes may get temporarily worse). Yes I did make accommodations for my children such that they did not lose–or avoid any win/lose situation. The major emotions that results weren’t worth it. Yes, if they did lose, I was right there to emotionally comfort them and help them untangle all those emotions. But I again did go out of my way to prevent the situation where they lost. And I find now, at 6, my son has no problem with losing. He’ll even say that things “aren’t about winning” or “this isn’t a race” and he faithfully follows the rules of the game, even if he loses, and yes he always wanted to cheat all during his preschool years.

I propose that not being able to lose a game is age related and if you just ride it out, they grow out of it. You don’t need to let a 5 year old lose a game to teach a life lesson. They aren’t mature enough to fully process it. And ironically this is the entire point of MacNamara’s book: they are immature when they are little and we shouldn’t rush them into being adults. Yet she is advocating directly here that we thump them on the head and let them be out of sorts when they lose a game, for the sake of not growing up to be entitled as she writes here:

One of the fastest ways to create an “entitled” or “spoiled” child is to circumvent the adaptive process and prevent feelings of upset from occurring about all the things they cannot change. The character Veruca Salt in Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory is the epitome of such a child. She orders her parents around continually: “I want it, and I want it now, Daddy!”

This view that “shielding” children creates entitlement is utterly prejudiced. Notice her weak argument above. Comparing a child to Veruca Salt in Willy Wonka gets your point across but it’s not an argument. It also unnecessarily raises fear. I notice that pretty much every bad parenting thought has this kind of fear hanging over it: your child will turn out bad unless ….

The reason why children grow up entitled or other poor ways is not because they were loved too much or rescued too much or any other shallow reason. Children grow up with problems, including entitlement, due to trauma. Physical and emotional abuse create problems. I promise I will never raise fear in parents, such as seen above, though I will always be unequivocally opposed to any amount of trauma and its inevitable results. I look forward to when all psychologists get serious and focused about dealing with trauma.

I could go on and on about “boundaries” but the pattern is always the same. Any time a parent “lovingly” overrides a child, it isn’t a good thing. Why does a parent need to make a child wear a coat? What message does it send that they can’t dress to their comfort level? I can agree that sometimes a parent does override a child’s decision, but the reasons are usually unfortunate. As I write this, earlier, I had to take my daughter screaming out of an indoor playground as she wouldn’t follow me. I regretted that I had to do that. Looking back though, we had forgot her favorite stuffed animal there. Maybe that’s what had her so upset but she couldn’t articulate it. Let’s say who it is that needs boundaries when we limit children’s behavior: we as parents need the boundary. I was the one who wanted to leave the playground, not my daughter. And I should have talked with her more (it was hard: the place was loud). There are ways to approach children that allows us to get our needs met as parents that still respect children. What I am describing is, yes, a negotiation-based approach. Yes, I am, as the parent, in the lead when it comes to mentorship, caregiving, and maturity, but when it comes to needs, I am equal with my children. Yes this means challenging hierarchical relationships. If you want to read a book that totally takes this kind of authoritarian relationship to task, please read Dr. Gordon’s Parent Effectiveness Training.

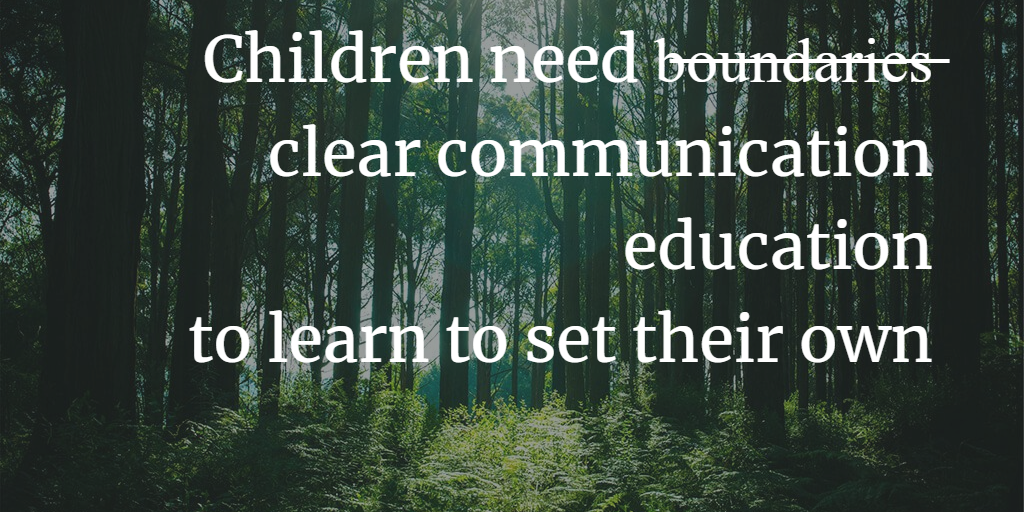

Children don’t “need” boundaries. Whatever is meant in that statement is something else. They need education, mentorship, to learn to set their own, to know what you expect of them, to have healthy habits modeled for them (i.e., no you don’t always get the snack at the impulse section in the grocery store.) Get specific when you talk. You might find that the stuff that they really need is all stuff that contributes to their growth and revolves primarily around education.

Now on to the second point that I am challenging: that parents should “ignore” children’s stages.

It is one of my biggest hopes that my work brings an end to the idea that children are “manipulating” adults when they go through these notorious stages. They are not seeking “attention” (a loaded term) or being spoiled or selfish. Rather they are seeking necessary connection.

On one hand, the idea of “ignoring” children’s stages has good things about it. Typically when a child is acting out, a mom might say, “It’s a stage. Don’t worry about it.” I applaud this as we are thus getting away from punishing or trying to correct a natural stage. But what I take issue with is the idea that we ignore these stages to “not feed the attention” or to “not reward bad behavior.” Several psychologists say to “hold space” for the child and not go to them while they “ride out” the emotion. This is in effect abandoning a child in need.

My work documents the very times when children act out, which are then usually followed by amazing growth. In studying these milestones and in watching my own children, I came to the conclusion that these times of turmoil, in which children literally cling to their parents or evoke their parent’s attention in some way, are the child begging an adult to come to them at a developmentally critical time. They make their presence more than known. The behaviors change from milestone to milestone but at each one, they draw an adult to them.

Humans are amazingly adaptive creatures. We can live in just about any climate or culture–but we need a huge investment to understand how to live in that environment. The children who were able to stick out and get adults to come to them seem to be the ones who have survived the evolutionary process. At each milestone, in which children act out, whine, grab you, block you from moving, become jealous, etc., I advocate that you go to them. Stop “ignoring” these stages. There is amazing growth going on. You are missing a lot of you ignore them.

We can use these stages to develop robust parenting philosophies. At the summaries on my website (under “Child Development”) I have “surviving” and “thriving” sections. I talk about using an understanding of the milestone to deal with the difficult behavior (surviving) then turning the new abilities into educational opportunities (thriving). It’s very nuanced and so I must refer you to the summaries, which are a growing body of thought.

I see these stages as something to understand. I see negative emotions as a sign that my children need me. I go to them. Sure sometimes I can’t do anything. Most times I can. And in being present, I gain extremely valuable insight.

I think the results have been astounding. My children could read at young ages–not because I necessarily explicitly taught them to read but because I followed their clear interests at each milestone. Early education is not abusive to the child: this is one of those thoughts that needs challenged and challenged hard to unleash children’s full potential! My children love math and play numbers like notes on a piano. They have photographic memories when it comes to science and history facts. They love to create and draw. And, what is most important to me, is they have astounding emotional maturity and conflict resolution skills.

To get these kind of results, we must remove the last barriers in the way of reaching children’s full potential! They don’t need boundaries and stop ignoring their stages. Let’s remove all barriers between us and our children and their needs, internal growth, and potential. This is the heart and soul of my book series, Misbehavior is Growth. See my first book, Misbehavior is Growth: An Observant Parent’s Guide to the Toddler Years

This article is one of the biggest risks I’ve taken here at The Observant Mom: directly challenging popular thought. I have been told by everyone who has read Misbehavior is Growth that my message is radical and new but that it is the right path forward. If you agree with that, please share this article. If you want to see parents have better understanding of their children, yet more acceptance of their children, and to unleash the potential by understanding these cycles, please share this article and maybe with a positive note about it. Thank you!

Drop me a line if you want at helloamber@gmail.com. Follow me on Facebook at “The Observant Mom.”

Thank you so much for taking that leap with this article. After recently reading rest play grow and other related, mostly wonderfully filled books, I was feeling incredibly stressed and pressured about the subjects of futility and children needing boundaries. This article at this time has set my thinking beautifully straight and meets precisely the feelings inside me that were screaming please trust me on this!