The main goal of education in the preschool years–other than fostering the massive development in social and moral understanding at that time–is concept formation. I describe it as The Three Little Bears Principle: by using directly observable or tangible objects, concepts are isolated. An ideal lesson is for example teaching temperature by having the child touch water that cold, warm, and (moderately) hot. The goal of elementary education expands on this greatly but also brings great intellectual organization of the inter-connected nature of subjects. In the elementary years, I seek to teach the spine of all subject areas.

In the preschool years, for the topic of properties of material, I teach shiny versus dull, hard versus soft, etc. In the elementary years, I introduce the periodic table, which organizes the elements. In the preschool years, I tell many stories. In the elementary years, I tell the entire history of the world in story format along with putting pictures of major events on a timeline. In the preschool years, I teach reading. In the elementary years, we start to diagram sentences. In the preschool years, I teach the parts of a plant, in the elementary years I teach the carbon cycle. In the preschool years, I teach animals and some interesting facts about each. In the elementary years, I teach the animal kingdom hierarchy. In the preschool years, I teach physics definitions, such as pressure and force. In the elementary years, I teach some of the most basic relationships among those terms. In the preschool years, we play with numbers up to 100. In the elementary years, numbers are turned into nothing short of a fun game, playing with them as if they were notes on a piano.

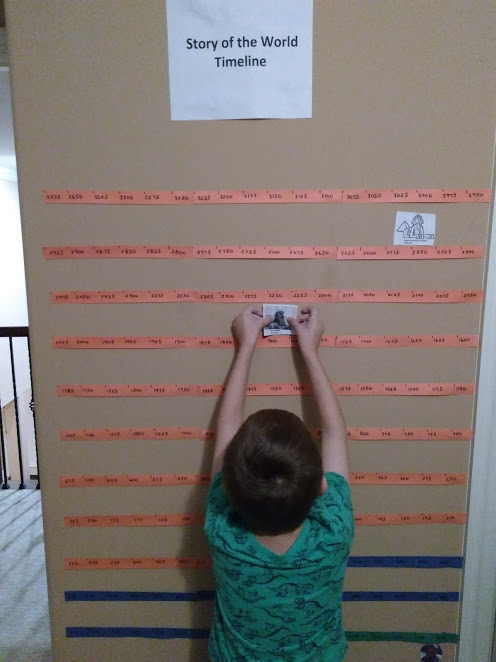

This is what I mean by the “spine” of every topic: the basic overall structure of the topic. For instance, in history, a fantastic activity was to put up a history timeline as we read short stories of history in chronological order. This was the start of ours:

What I love about this approach is it grounds the child. After we did this timeline, we drilled in further into parts of it. For instance, my son loves ancient Rome. When we read a book about Romulus, it wasn’t just a random story. He could go to our timeline and point to exactly the time when the story was relevant. Similarly, as we read the many, many stories that history provides, it will not feel like a random smattering of stories that could go on infinitely with no end, but rather is a drilling in of a particular time period. Sure, we can read about history endlessly. But at any point, we are getting more precise. It takes the enormity of history and put it in the palm of your hand, or, in this case, about 3′ X 6′ of wall. This is the liberating effect of properly organized concepts.

I am a bit hesitant about approaches that pick a random, specific topic and explain it. For instance, to ask a child “Are bones bendy?” “Why are cabbages green?” “What insect glows?” As an adult, when I hear these questions, which one could make up endlessly, I never know the answer or, rather, I don’t know why the question is being asked, as if there is something deeper than the obvious. The answers are often dissatisfying–a glowworm is an answer to an insect the glows but so do fireflies. My young child was not wrong his answer but the book we read could make him feel that way. These random questions make me feel intellectually inferior and like learning is scattered and endless. It’s not the feeling I want to create. I want my children to feel intellectually potent not intellectually distressed. I love this approach of providing the spine of a topic, which, among other things, provides such a clear categorization of a topic as to allow all future information about it to be well categorized in one’s mind. After presenting the spine of a topic, questions can play a hugely beneficial role. I make points undeniably clear by asking somewhat ridiculous questions like “Can alligators build bridges?” But only after the topic has been thoroughly covered, with my child’s mind ripe, do I ask such questions.

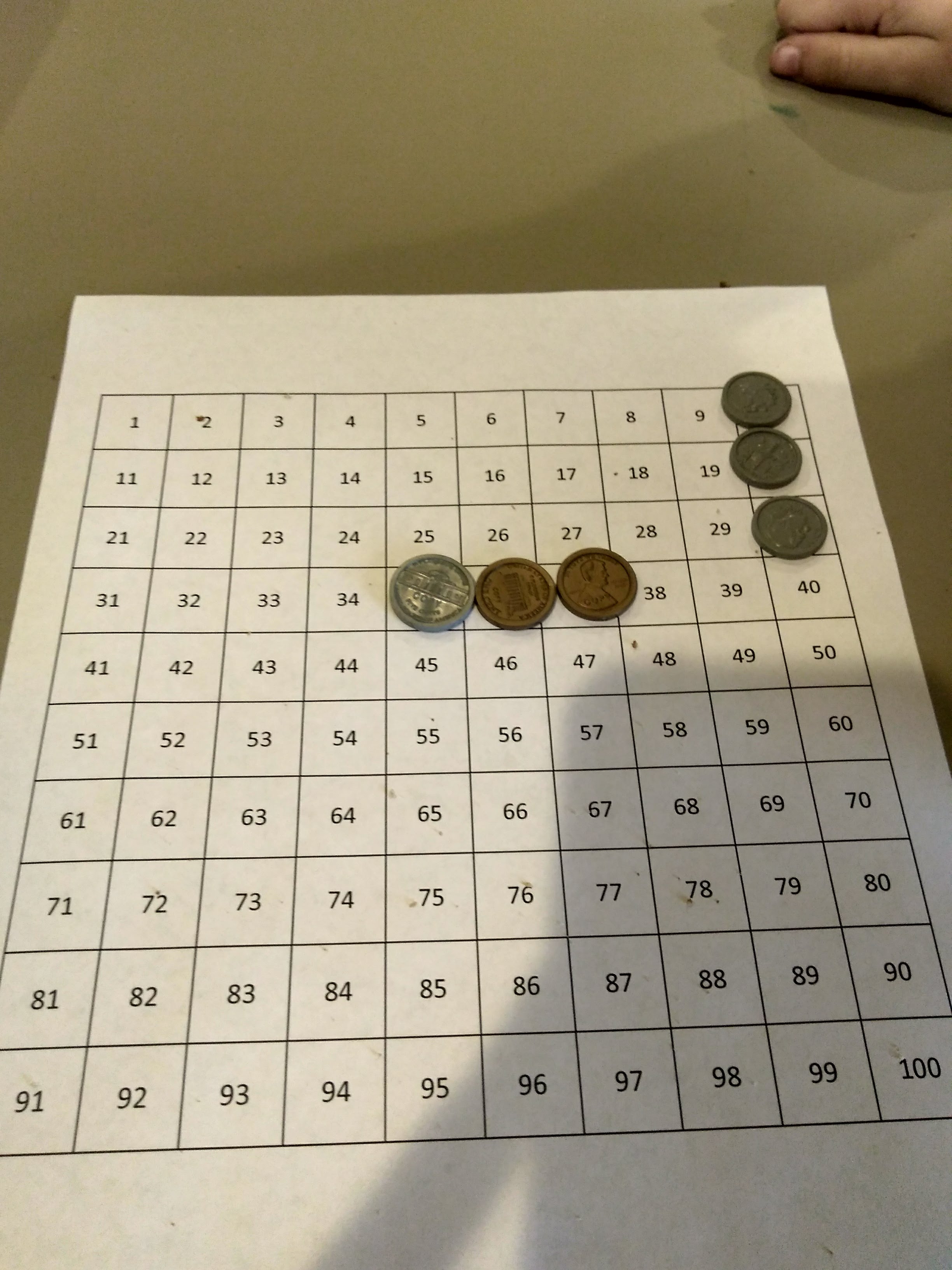

To implement this approach, you will find I love to use grids and diagrams and more grids. When you realize the power of a grid in learning, you will notice how often they are used in daily life. A calendar for instance is a form of a grid, to organize calendar days. A most powerful way to teach numbers up to 100 is to have a child simply write them out on a 10 x 10 grid, with the right answer right before them. I love to give my children a peg board–a sort of grid–to put perl beads on, which can expand their mind as they think of patterns to put on it. Our history timeline previously mentioned is essentially a diagram of history. When we diagram sentences, we bring intellectual clarity to grammar. I teach carbon cycles, life cycles, and weather patterns with diagrams.

When I worked in software, I saw the power of a diagram routinely. When engineers would be trying to think through a problem and were turning their wheels, stumbling over definitions, I would draw the problem out on my beloved notebook (which went with me everywhere). Every single time, people crowded around the diagram, using it to think, and draw on. Diagrams are powerful. You would be amazed by how easy most concepts are if you have a handy diagram. Figure this out, and you’ll almost always be the smartest person in the room.

A great way to teach about percentages, money, and more

One other aspect of elementary education is that students can imagine things that aren’t in sight. They can imagine atoms or weather patterns. This is also a distinction from preschool to the elementary years. (Although in the preschool years they can certainly understand planets and dinosaurs.)

Another aspect of quality teaching is to teach things in a way that moves. With history, this is easy. The stories move one after the other as the dates go on and on. Here is a fun lesson: how does water drain? When it rains, water drains from your yard to somewhere, perhaps a stream, then to a river. What would the path of a toy sailboat let loose here be!? Using a map, a type of diagram, you can follow the path and learn about this topic. I consistently look for activities that have life and movement in them, such as taking a “tour” through the body. Diagrams help with this too.

Although I stress teaching the spine, the broad overview of the topic, this doesn’t mean that these years are exclusive to the broad overview. Quite contrary, with such a solid base, the child can dive in easily. My son had an encyclopedic knowledge of many topics. This method allows for such extraordinary retention of knowledge that this is possible. I let him watch whatever educational videos he wanted. He had no problem integrating the information with his existing knowledge set.

As the later elementary years set in, I expect much more hands-on, project-based learning as children use this information, dive in, and develop, as one skill, prose. I look forward to learning about this!

Working on Misbehavior is Growth: The Early Elementary Years now. See my book Misbehavior is Growth: An Observant Parent’s Guide to the Toddler Years.

Find my on Facebook as “The Observant Mom.”