Perhaps the most radical way that my parenting approach differs from others is that I do not think children “need” boundaries. Children don’t need boundaries; parents do. This is the crux of the issue: who owns the issue and who benefits. It’s a subtle shift in thinking but it has major ramifications in approach. When a parent doesn’t want the child to get into the flour or climb a tree or bang on the walls, it is to satisfy the adult’s needs not the child’s.

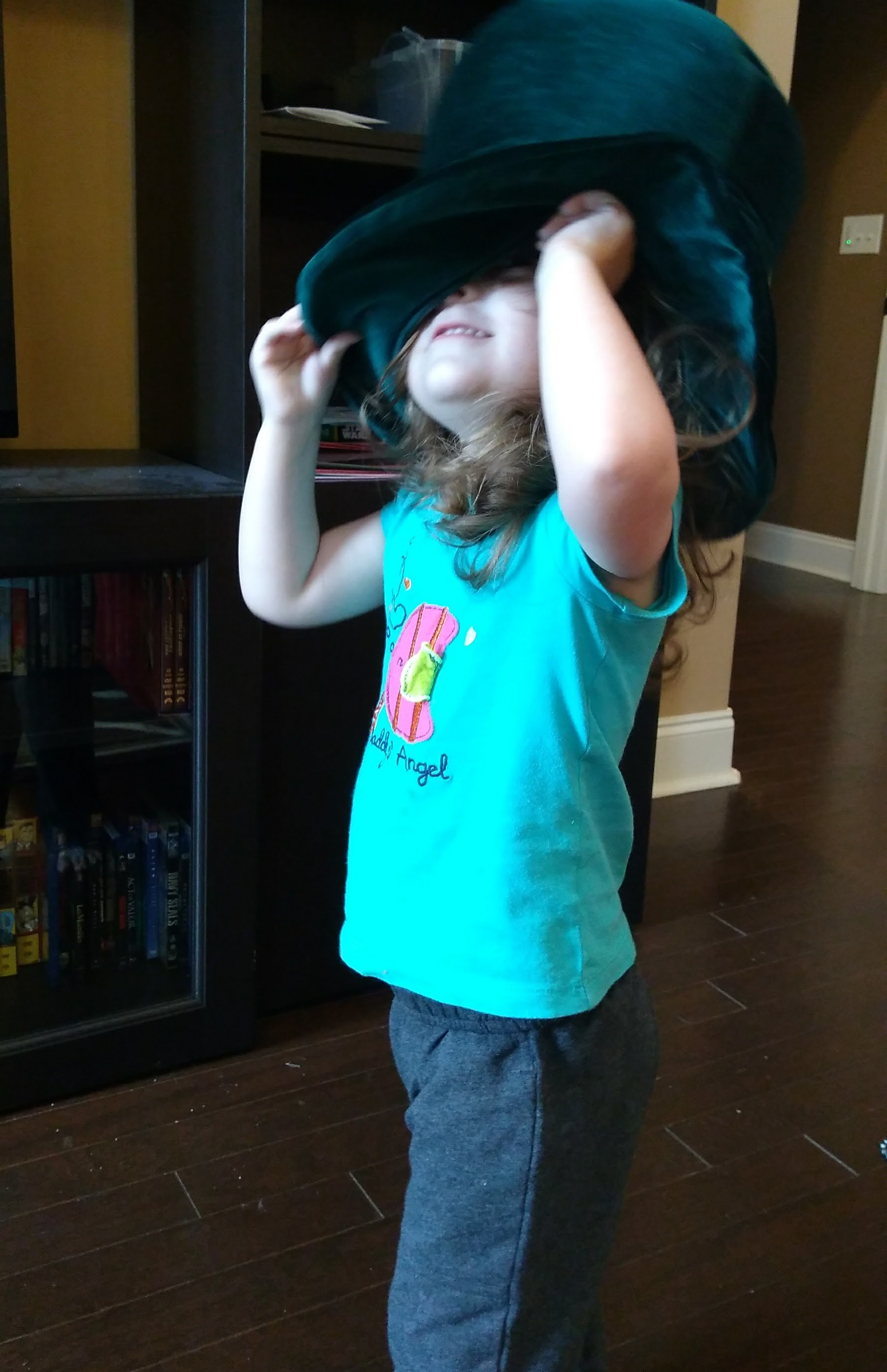

A child’s need, usually, is to play, learn, and grow. If a child is banging into walls because they are riding their tricycle in the house, their need at the moment is to develop their gross motor or navigational skills. It’s the parent’s need to spare their walls. The child in that exact moment may benefit from a lesson about walls–or they may not–it really depends on where they are at in their developmental time table. In the late twos, I start to make heavy use of I statements to communicate such concerns and younger than this, I use redirection. Both are effective ways to curb undesired behavior and both recognize that the parent, not the child, owns the problem. They are respectful approaches that gives the child what they need when it comes to having an adult enforce something with them: a firm, calm, and clear approach.

Sure, a parent needs to stop a child from going into the road (by the way, I am dead serious when I say I want to move to a parenting eco-village: no roads!). The benefit to the child is not that their movement was restricted; the benefit to the child is that they are safe. Sure, a child needs to hear what a parent expects of them. It’s not because they child likes having to get dressed at a particular time (when they would rather be playing); it’s a benefit because they get honest communication from their parent. Children do not “need” to have limits set on them, nor do they especially like it. Ask anyone in the midst of trying to get a defiant child’s shoes on if it seems like setting this limit is meeting some deep developmental need to actually like having their choices overridden.

Children primarily need freedom and acceptance. This is the environment that they thrive in. One of the problems with “needing boundaries” is it fuses together the development of the child with an in-the-moment problem. This can create an explosive situation. While you are dealing with a child who won’t put their cup away, you might also be thinking, “You need to learn this so you grow up to be responsible! I can’t have you being lazy! I need to set this limit on you.” This message will be deeply felt by the child: you don’t approve of them. It will make you exasperated as you try to enforce it. It gets elevated to a much bigger problem than it is. It needs to be demoted to what it is: a cup is out.

Further and this is probably the biggest issue, setting limits is that: it’s limiting. A parent has decided x, y, z behaviors are acceptable or unacceptable and enforces it. I find a better approach is one of assuming abundance–rather, of generating solutions. I once had to stop my daughter from eating a frozen fruit popsicle that had been reserved for her brother. I started to tell her, “Your options are this and this, you CAN’T have the popsicle.” It made her cry harder. When I switched my language to, “It looks like you really want this pink popsicle. Let’s think of ALL the things that are pink that you can have: there’s pink yogurt and pink strawberries and … ” she stopped crying and happily picked from the long list of stuff we were thinking of that she could have. About 99% of my parenting success, when I do have success, is that in the moment, I’m not thinking about how to get my child to gladly comply with the exact thing I am enforcing but rather I’m thinking in highly creative ways of what might resolve the situation. I’m thinking about creative words I can say or creative solutions I can find that will satisfy their and my need. I can tell when I am only putting half my effort into it and when I need to lean in harder.

My approach to parenting, as is the title of this website, is to be observant of the child. There is a huge, untapped potential in most children. It’s about tapping into that more than anything. While they are riding their tricycle around and the parent decided to yell at or punish the child or work directly on “respect,” they might have missed that actually the child has extremely impressive steering skills. I statements, redirection, and other such tools that do not directly try to limit or alter the child, allow the activity to continue, but in some way that is respectful of the parent’s needs. This is what I’d like to see: a constant discussion about how we can keep children growing to their potential, not how we can benevolently limit their behavior.

See my book Misbehavior is Growth: An Observant Parent’s Guide to the Toddler Years