This is part of 3-part series where I am discussing the research I’ve been doing on child development. In Part 1, I talked about how misbehavior is inevitable. In part 2, I talked about how misbehavior is manageable. If I could convince (more) people of these 2 things alone, I would be really happy.

This third point is my most radical and my most important. From people who have read my book, they say that they think this point is a very new way of looking at parenting but that they agree it is the right way. And it is this: that misbehavior is growth.

By misbehavior is growth, I mean that the difficult behavior is not just random. There is something growing in the child. And this has big implications.

If a person followed along with my work and part 1 and part 2, they are likely to readily agree that most difficult times with children are a stage. They are likely very on board that we need to develop patience and tools to get through them. This is the #1 thing my work currently promotes: more patience for the parent as they get through these stages.

However, if it were to stop there, a person might develop the popular belief today that when children “misbehave” during these stages that you should ignore them–ignore the child because they are just “seeking attention.” The argument is that giving them attention during these stages will “reward bad behavior.” This is what I am directly challenging.

My take on this “bad” behavior is that it is the child not seeking “attention,” which is a loaded word, but rather the child is seeking connection. Children seem to be designed to draw adults or others to them at these developmentally critical times. They purposely grab you or evoke a reaction from you in some way. And in my opinion, that makes sense. Humans are highly flexible animals. We have lived for thousands of years in many different cultures and places. A human must be taught by other humans how to survive. As an extreme example, a child born in a tribal culture will be taught a completely different set of values than one born in modern America. This need for guidance is constant all throughout the developing years. And so when children act up at these stages, I advocate that you don’t ignore them, but rather go to them and give them love and comfort and the connection they are basically begging for. They need you.

Further, these moments of what could be extreme negativity can actual turn into something very positive. If you know what skill they are working on, using that knowledge is often the very thing that can help calm the child down. For instance, in the early Preschool Milestones, a very effective way to calm a meltdown is to tell them their favorite story. Now, not only has the meltdown dissipated but you are also working on reading comprehension. It can take moments when you are simply surviving and turn them into moments where you are thriving. I contend that these times are critical to development. Treat them wisely.

Further, an entire educational paradigm can be built around the milestones. We adults can understand what is growing and be ready with games, challenges, education, and activities. The potential that is there is enormous and almost entirely untapped.

For instance, in the toddler years, you can teach a child how to read. First, this presupposes that they have an interest in doing so. The potential is there and if the interest is also there, you can do activities to promote this skill. I don’t want you to feel pressured. I don’t want you to feel like you are failing if your child isn’t doing this in the toddler years. Everything about education should be a joy. The goal is to tap in to the inner teacher of the child and gently guide it. Using this approach, there are no battles when it comes to education. If something is working, you do it. If something is not, you stop. This is my unyielding guide to all of my parenting and also why I think I am able to do this work. I fight nothing with my children. I assume they are developmentally where they need to be and I give them the freedom to grow as their own internal drive takes them. But certainly I teach them also; I just make sure it’s in alignment with their interest and abilities with no battles (a point worth repeating). I advocate at all times slow, clear lessons.

I have many other examples of skills that can be taught using the milestones. For instance, in the early 5s, children can do much more math than previously thought. They can understand how something changes over some continuum. This means they can understand bar graphs. They can understand angles. I taught my son this at these ages and he showed he understood them later when he solved challenging logic puzzles using these concepts.

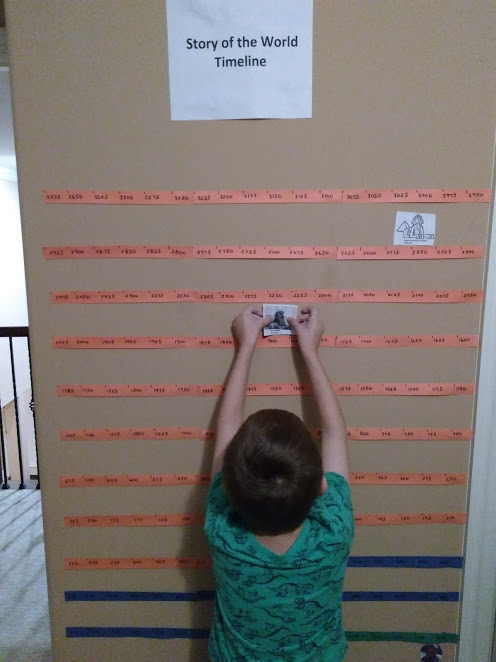

Another example is when to teach history. At around 5 years, 5 months, children become intensely interested in adult humans and their stories. It’s a great time to teach history. Another example, the preschool years are a great time to do science experiments and teach about the natural world. This is not common knowledge. This is not how education is typically approached.

I want to give further evidence to what I am saying here. There was an article in Time Magazine called Super Families. It is the story of “nine American families” with children who “all went on to extraordinary success in different fields.” The families were all very different except that every single child grew up to be a mega success. They identified 6 major factors in what drove that success. I’d like to focus on two major points.

The first is that the families highly valued education. The second of the six factors was “Parent-Teacher.” The article describes that 7 out of the 9 families had a parent who was a teacher. The parents valued early education. Just one quote from the article, “Parents in these families instinctively understood the importance of at-home instruction decades before researchers established the merits of early education. Their children recalled early supplementary lessons, books read aloud, regular library trips and even at-home worksheets to give them an early boost in school.”

This probably seem intuitive as a good parenting principle. I will say that some people argue with me over it. Some say that parenting is about setting an example not explicit teaching. I disagree. This point of explicit instruction is in alignment with my idea that misbehavior is growth: my point is to invest in the new abilities as they grow. This point may be slightly controversial; however it is much less controversial than my second point.

My second point is that the families featured had a high tolerance for misbehavior. The introduction says, “most said they grew up with much more freedom than their friends did.” The fourth quality was entitled “Controlled Chaos.” The children describe getting into fights, doing drugs, putting glue in hair, tricking strangers, cutting school, shoplifting .. you get the idea. The sixth quality was “Free Range Childhood.” The children were given lots of freedom. They were allowed to ride their bikes all over and skip school. The parents did not monitor them or make them do homework.

So this point is much more controversial. It is the opposite of what we hear is the ideal parent. An ideal parent has their children under control right? They keep them on the right path, right? Some data says the opposite. And it is in alignment with my research: children by nature will misbehave and they need the freedom to be allowed to do so.

But here’s something that my research can help with. By knowing the milestones and knowing the potential, we can invest in skills at very early ages. So I want to give the example of violence among siblings. One of the things I am most excited about with my work is the young ages at which you can teach healthy conflict resolution. You can teach it in the preschool years. My children are remarkable at it, at ages 6 and 3. So if you impart this skill set at an early age, I believe that later, you’ll have less violent interactions amongst siblings.

So this is how my research can take healthy parenting to the next level: you can still give children that freedom that they need to make mistakes, test, and explore but in such a way that there are less frustrations. Less calls from the principal. Notice I didn’t say no calls. I said less! But this is the healing power of science and this work. You can have the best of more worlds: extending freedom but also keeping the peace. You have both a better end product and a better process to get there.

So drop me a line. What do you think? This is the heart and soul of Misbehavior is Growth. See my work in the “Child Development” page up above. See the “Surviving” and “Thriving” sections which seek to show off this idea with examples. See my first book on this, Misbehavior is Growth: An Observant Parent’s Guide to the Toddler Years. Please share this article!

One thought on “Child Development Part 3: Misbehavior is Growth”