I read in the introduction to The Writing Revolution, a brilliant book by Judith Hochman, that younger students are asked to write and teachers are prepared to help them with their writing, but the assignments that students turn in are so filled with errors that the teachers cannot keep up. The teachers of younger students assume teachers at older ages will help fix the errors, as they find them. The teachers at older ages, however, assume that this should have been taught at younger ages. Students are caught in a No Man’s Land, where no one is really overseeing their writing skills. And as a homeschool mom very dedicated to trying out different educational approaches I am wondering: maybe we’re teaching writing at too young of an age?

I read a lot and I mean a lot about education. I’ve read several different theories on how to teaching the skill of writing, and I’ve tried many. I’ve done many, many hands-on Montessori grammar lessons. I don’t regret doing these. If anything, they taught words, and that’s always my goal when educating. A word represents a concept in reality, and my goal is to tie that word to what it is in reality. If I am teaching rough and smooth, I’ll get out glossy paper versus sandpaper to teach it, and I’ll write the words on slips of paper next to it. A constant tying of ideas to reality, that’s what I do, and that’s what I want to do with writing, too. We did some sentence diagramming, using the Montessori symbols for it. I bought one program, “Daily Grammar Practice.” It was illogically laid out, and my son lost interest after maybe three weeks of lessons. I went to Khan Academy and was a little blown over by how much writing they expected young students to do, such as writing a summary paragraph, in first grade. Where are the lessons where they teach a child to capitalize the word, “I”?

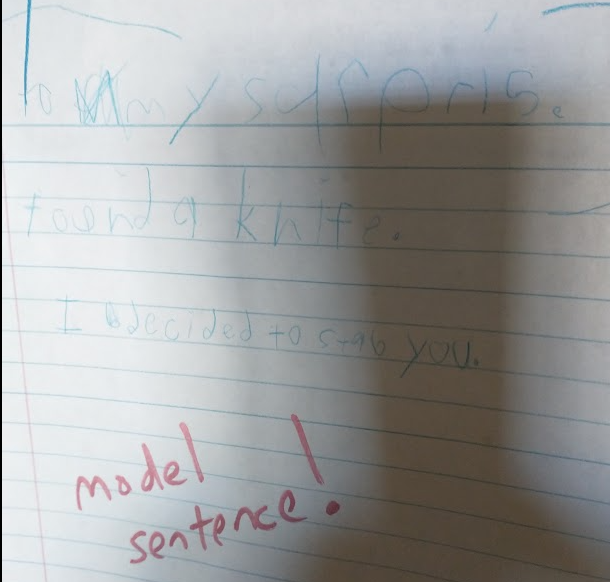

I also, most recently, bought the book Patterns of Power. We did this for an entire semester. In this book, you give a child a sentence from children’s literature, highlighting a particular grammar concept and ask, “What do you notice?” So, honestly, I had to amend this. Instead, I put two sentences, highlighting something similar or different, and then asked what they noticed. Just asking what they noticed, I found, was too open-ended. There is an answer you want them to come to. Why are we letting them sort of languish about it? At any rate, we did this weekly. I also had a few activities for them to correct sentences and then write a sentence. They would write a pretty good sentence, usually, if just presented the lesson. Sometimes they absolutely did NOT want to write a sentence, and expressed as much, in their sentences. And, after all this, after doing the whole book, when I asked them to write in a more free style way, without having just done a lesson, they by and large forgot most of what they were taught.

I found that *my* writing improved after all these lessons. However, I am an adult with decades worth of practice writing. I was able to draw on my database of knowledge and apply the new knowledge to my new writing. Indeed, grammar needs to be actively taught. In fact, it probably needs to be taught over and over again. Skills can get rusty. Your thoughts probably become more complex. You might need more tools. But I digress. What I basically noticed is that most grammar programs out there seem to assume that children are given a massive number of overwhelming writing assignments, and they are coming in with their program to kind of make things a bit better. Or, at any rate, they are assuming a child is already writing quite a bit, and they are here to then teach grammar. What is out there for me, the homeschool mom, the one willing to try to do things right, right away?

I am not sure, but I think I got the thought from Montessori that if you taught grammar in the early years, the sentences children write would come out beautifully right away. It’s amazing that I, the author of Misbehavior is Growth, could have thought that. Where I am at now is that, indeed, children probably need to be writing quite a bit, and you teach and correct grammar as they go. This is how I’ve done it, right? I’ve been able to change my writing with new information about how to write better. I do, however, still think that giving children too much too soon can set in sloppy habits, which is what I think I was trying to avoid.

But here is where my work on child development work kicks in. I didn’t really find that children are able to handle critical feedback about their writing until about age 9 or 10. Maybe this depends on the child, but still–for those children, we should consider this. Before this, I found children are very touchy about being told they made mistakes. At 7, for instance, both of my older children got wildly upset at least once that they didn’t know how to spell something when they went to write it. (This is why I do indeed think spelling should be actively taught, and we do a spelling list if not two per week.) But, before age 10, my children really didn’t like having their writing corrected; in fact they barely liked to write.

What I found children did like, before age 10, was having stories read to them and reading. Even newborns like hearing stories (and songs) and so do toddlers, but in their early 5s, children have a very strong ability to imagine themselves in another place or time. This skill just continues to grow. In their late 5s, they can follow a story as if they are watching a football game and eventually, they can keep up with the same story night after night. In their early 7s, they start to take on big goals, and they might put down entire book series, by themselves. My oldest read entire history series, several times over. At 7, my daughter put down the entire Harry Potter series. Their knowledge base is massive. I never game them tests over any of it. I didn’t frustrate them with too many writing assignments. Instead, they were an information sponge, for years. And having a strong knowledge of a topic naturally makes a person a better writer, right?

By the way, I DO think reading can be taught at younger ages. I found all of my children were reading well by age 5. This includes my youngest, who is a more rambunctious little boy who wasn’t nearly as into “academic” things as his older two siblings were. What I did is I taught words simply. If they wanted to know what a word was, I just said it. “Women” reads as “women.” I did teach letters and sounds. But, after that, I got off the phonics train. I didn’t make them sound out “W-o-m-e-n.” My children effortlessly learned to read. They learned it from books, videos, and signs everywhere. And this sets them up to be the kind of information sponge as I just described. I kind of think the ages of 5-9 can be spent mostly reading stories, doing science experiments, playing games (including math games), playing sports, and letting children pleasure read.

At age 10, about fifth grade, I find it is getting far easier to teach my oldest how to write. His sentences occasionally come out correct, with neat penmanship. By the way, I do believe in working on penmanship weekly, which for us amounts to copying only one page with a few words on it. My oldest also has no issue with me correcting his mistakes. He is very reasonable about it. In fact, when we get Microsoft Word, he’s determined to make all those squiggly lines telling you you made a mistake go away. I do very much agree with the premise of The Writing Revolution, that the sentence is king. How can you write a good paragraph without writing a strong sentence? This is what helps me write: does the sentence I just wrote make sense? I describe it sometimes as making sure every grain of sand fits with the rest of the beach. But, anyway, this is what I’m not on board with a massive amount of essay writing. I like the sentence activities recommended in The Writing Revolution.

Writing is kind of the wrapping around the present. There are the ideas in your head, and then there is how they come out on paper. We have various conventions to make those ideas come out on paper in a way that is readable by other people. The way a person writes and a way a person talks are different. They have to be. Children are just developing their ability to take in large amounts of data and explain them at young ages. The lion’s share of the work is being done by their own mind, which has a voracious desire to learn what it wants to learn and process it the way it wants to process it. Maybe we could let the brain do that during these elementary years, roughly ages 5 – 9? And maybe we shouldn’t worry too terribly much about writing conventions until children are age 10 or over, when they are more capable of taking in criticism and even have a healthy respect for making a well-constructed sentence. Sincerely, I want my children to see the beauty of grammar. The rules of grammar really do make sense, even if they need broken occasionally. Grammar is a way to help them communicate eloquently; not a badgering set of rules to learn.

If we waited to teach grammar, and I mean pretty much all of it, until older ages (fifth grade), maybe students wouldn’t hand in assignments with so many mistakes that teachers are too overwhelmed to do anything about. Maybe the expectation should be that the teachers of older students teach it.